The reality is that most swords with a cut and thrust blade can serve as a sidesword, and swords that allowed for a fighter to wrap his finger around the guard can and were used in the Italian fencing traditions. But if we stop to think of that ideal sidesword, that Spada da Lato that we associate with the Bolognese fencing tradition, an image starts to appear in our minds, and a certain aesthetics for the hilt emerges.

We want some complexity compared to a basic cruciform hilt (even if cruciform hilts were still used when Bolognese traditions emerged), but not as developed as we see on later rapiers. Let’s add the hilt elements, one by one and, and see the impact each makes on the use of the sword.

Quillons that are straight make sense to keep the sword symmetrical and ambidextrous. But S-shaped quillons that come out of the plane of the blade sounds better. The top quillon needs to bend towards the outside of the hand. An S-shape for the quillons in the plane of the blade is seen sometimes, and the combination of the two can give an exotic look, if done right. With chirality in play, we now have a sword designed specifically for right-handed people (as good Christians, we naturally don’t associate with sinister people, but we do learn to fight against their wicked plays). Note that at this point, we can rotate the sword in our hand and still access both edges of the blade as the true edge.

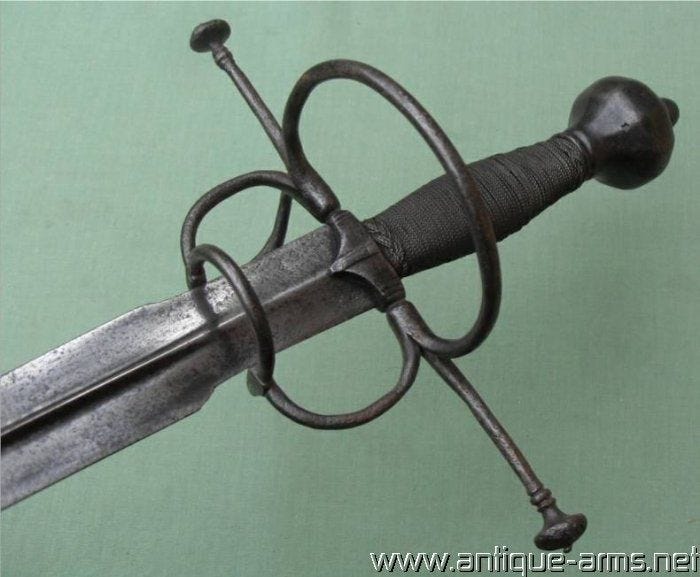

Finger-rings that are joined by a side-port ring on the outside of the hand sounds like a must. We may accept finials instead of a ring, but only as a second choice. Note that while the side-port on the outside has a role in parries, it also has a role in reinforcing the structure of the finger-rings. An additional reinforcement sweep on the inside of the hand can be seen connecting the tip of the finger-rings, especially if finials are used. At this point, the true edge and the false edge are dictated by the morphology of the sword, and our choice in rotating the sword in our hand is lost if we want to stay true to the intent behind the design.

As long as we have a side-port, adding a knuckle bow will not introduce additional limitation on which edge we will use as the true edge. However, we may choose to dispense with the knuckle bow if we want more mobility for our hands. And as long as we keep the quillons straight, dispensing with the knuckle bow also allows for an ambidextrous use of the sword, while keeping the side-rings on the outside of the hand in both cases.

If we feel that our hands are still exposed, a larger side-ring at the level of the quillons may be added, and even simple sweeps that connect the finger rings and the cross-guard on the inside of the hand. Some restrained needs to be exercised at this point, or we will end up with a fully developed swept-hilt sword.

In regard to grips, they must have a reasonable length, since we are expected to finger the cross-guard. However, a shorter grip will allow for the base of the hand to interact with the pommel, in which case, a flatter disk pommel is to be preferred.

With the thoughts behind different choices made verbose, I want to do another dive into Czerny’s auction house, and highlight sideswords that would feel right for the Bolognese tradition. The advantage of using an auction house is to get the feel for pieces that have not been curated by museums. We will then proceed to look at famous sidesword that are held in museums, estimate some dimensions where possible, and insert some context regarding the trainer and the reproduction market.

Czerny’s

The Perfect Sidesword

Probably my favourite looking Bolognese sidesword. Double-edged, straight blade with a centre fuller and a distinct ricasso. The blade bears the inscription "MEDIOLANUM" on one side, and the date "AN 1546" on the other. The S-shaped quillons have a ribbed leaf motif, carried over to the side-port ring. The nice round pommel is carved like a shell, or as the rays of a rising sun, but only on the exterior side, being left plain on the other side. The grip is covered with wire and has a pleasant twist to it. This Italian sidesword from c.1546 has a total length of 123.5 cm.

From the full length photo, we can estimate quite a long blade at 107cm. The width of the blade, above the ricasso, is estimated to be 3.25cm. The span of the quillon, from end to end, is 18cm, and the 8.5cm long grip is paired with a pommel of 5.7cm in diameter. We see that the blade is not overly broad, and that the grip size, flat pommel and quillon shape tells us to finger the guard when using this sword, just as seen in the drawing of that accompanies Marozzo's Opera Nova.

Restored Sidesword

Let’s look next at another design that screams Bolognese sidesword. At least I believe so, and so did people in the 19th century. While the cross-guard assembly and pommel are original, the blade and grip were added much later. Yet this restoration from the 19th century tells us that people shared the same ideas as us for the look of these swords. And the bud shaped pommel and twists in the quillons, knuckle bow and side-rings give a simple elegance look that is associated with sideswords.

Composite Sidesword

Let’s stick with a similar design on a composite European sidesword from the 16th century. Straight double-edged blade with a central fuller, with a hexagonal cross-section out of the ricasso that becomes lenticular towards the tip. The grip has a leather sleeve covering, done over risers. The bulbiform pommel with raised petal decoration looks to match well with the simple decorations on the side-rign and knuckle bow. The petal decoration is reminiscent of the “segno”, a footword diagram in Bolognese fencing. The side-port ring at the end of the finger-rings is either missing or was never present, in which case this is an atypical design choice. Either way, we can easily imagine it being present to obtain the desired image. Total length 116.5cm.

Bulbiform Sidesword

In yet another example from Czerny’s with a bulbiform pommel, we see an S-shaped design for the quillon in the plane of the blade. I am listing it to showcase that this was a design used in the period. In regard to the pommel, while it looks spherical, side-views of the sword show that it is in fact flatter towards the plane of the blade, presumably to facilitate its placement at the base of the hand.

Superb Bolognese Sidesword

From the Klingbeil collection, listed by Hermann Historica in 2012. This superb Bolognese sidesword, c.1530-50, has a heavy double-edged blade of flattened hexagonal section and a buliform pommel. The overall length is 107cm, the blade is 94.7cm long and 3.6cm wide, and the grip is 7.5cm long.

Unknown Sources

While I don’t know the sources for the next two examples, their hexagonal blades coming out of the ricasso, central fuller or twin fullers, S-shaped quillons with a ribbed leaf motif that is mimicked on the side-port ring, and pommels that complement beautifully the overall look and function of the swords, make me declare these as having that ideal Bolognese sidesword look we are looking for here.

The Luigi Marzoli Museum in Brescia

Without insisting, I want to showcase a sword that I understand is held in the Luigi Marzoli Museum in Brescia (while I couldn’t confirm this fact). Two aspects are of note. One is the relatively thin bars that make up the quillons, finger-rings and side-ports. The other is the central ridge on a blade with a pronounced hollow grind. These blades, that allow for a thin and sharp edge on spada da filo, were quite common and deserve a separate look into their use in the period.

Cleveland Museum of Art

We start the showcase of clearly curated examples, by looking at this beautiful Italian sidesword c.1550, with a russetted hilt and leather grip. The overall length is given to be 100cm and the weight is listed as 1000g. The museum lists the “grip” to be 11.5cm, which matches our estimate of the actual 7.5cm short grip and 4cm diameter round pommel. We note again that the petal decoration on the spherical looking pommel is reminiscent of the “segno” in the Bolognese fencing tradition. The length of individual quillions is provided as 6.3cm, and our estimate give us a 16cm wide spread from tip to tip. The short quillons is probably the most atypical choice for a Bolognese sidesword. The hexagonal blade is 87cm long and 3cm wide. We note that so far, where measurements were possible to estimate, we have only found blades narrower than 3.5cm, a threshold I saw as a minimum for a cut and thrust sword previous to this exploration.

The Wallace Collection

We look now at an Italian sidesword with chiselled hilt, c.1540. The total length is listed as 112.4cm. The length of the blade is given as 98.8cm, and the width of the blade at the top of the ricasso is listed as 2.8cm. The guard is 17.6cm wide, and we are give a balance point of 14.2cm, forward of the guard block.

We would be remiss not to mention the composite sidesword made by Florian Fortner, who took inspiration for his modern reproduction from this historical example. A rare case, where the new improves on the old.

The Met

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, possesses multiple examples of interesting, beautiful and historically relevant sideswords. Without putting too much weight on the names I will use to denote them, let’s go over the ones that match that Bolognese look we are after, and see what lessons we can learn from them.

Single-edged Sidesword

Italian sidesword, c.1490, of 104.5cm in total length and 1049g in weight, with an intricate silver hilt. The grip, made of silver plates, it’s one of the most striking features of this sword. While they appear flat, the side view pictures show a slight arch in the grip. While this may seem trivial at first, the slight sideways bulge of the grip makes for a much more secure grip when using the sword. This clearly expensive sword, that would have turned heads even in the period, is designed to be a martial sword. The small langet protruding from the finger ring, around the spine of the blade, is most likely a way to secure the sword in the scabbard, one that would terminate at that point. If true, this is a clever design choice to keep the sword in, while facilitating a quick extraction with a finger already wrapped around the guard.

Having access to a full length picture of the sword allows us to estimate the grip to be only 8.6cm long. The large pommel, estimated a bit under 7cm wide and 6cm tall, is of a convex wheel in shape. The size of the grip and shape of the pommel are conducive to having the pommel rest at the base of the hand. Together with the long langets present around the sides of the blade, a fine control of the sword is made possible in regard to rotating the blade around the longitudinal axis. The gentile S-shaped quillons of a generous 25.4cm in length would facilitate the protection of the hand. From the side-view pictures, we see that the quillons protrude to the side as much as the side-port ring. The sideways protection of an S-shape design should not be overlooked.

The length of the blade is given to be 88.3 cm, while the width of the blade in the ricasso is estimated to be a bit under 3.5cm, the widest blade we found so far. Only the last 34cm of the blade are double-edged, the rest being single edged with an asymmetrical three-fuller pattern. These choices would indicate a rigid blade on a nimble sword.

Looking at the Duelist (Configuration 2) trainer from Malleus Martialis, which shares the same design pedigree, and having an experience with the similarly shaped Marozzo (Configuration 2) trainer, I can say that a more pronounced convex profile for the pommel would have been a better choice (and probably a more expensive choice as well). A lesson that will be reinforced by the next example, is that a disk with an extreme convex profile needs to become a staple on Bolognese sidesword reproductions.

Charles V Sidesword

One of the most famous swords on this list, the rapier of Emperor Charles V (1500–1558). Not only the owner catches out attention, but also the sword’s maker, Francesco Negroli (Italian, Milan, ca. 1522–1600), renowned for his damascening skills, who with his brothers may be considered the most famous armourers of all time. The sword is dated c.1550–53, made in Milan using steel, gold, silver, and wood.

We are given a total length of 107.3cm, a weight of 1219g, and a quillon width of 16.5cm. The diamond profiled blade is 93cm in length and 3.25cm in width (only 2.6cm at ricasso). The short grip is 7.5cm long and 3cm wide at the largest point. The convex disk-like pommel is 5.6cm tall and 5.2cm wide. Based on these measurements, we again speculate that one would use this sidesword by fingering the guard, while allowing for the pommel to rest at the base of the hand. We note the use of finials for the side-port instead of a ring, which we associate more with a Spanish tradition, appropriate considering the owner of the sword.

The last picture, liberated from the internet, shows this sidesword together with other sideswords/rapiers held at The Met. A beautiful perspective that allows us to compare their size in regard to each other.

Brescia Sidesword

Italian sidesword c.1550, possibly from Brescia, with a weight of 1191g. The total length is 105.4 cm, of which 92.4 cm are taken by the blade. The width of the quillons is given to be 18.2 cm. While recognising that this style of fullers was used to showcase the mastery of the blade-smith, I am not a fan of the look. The one aspect that deserves note is the axisymmetric bulb-shape pommel, that most modern fencers may like.

Looking at the Manciolino Op.II trainer from Malleus Martialis, we see that this pommel makes for a comfortable and versatile choice, especially when a few cm are needed to fit in a glove.

Gilded Sidesword

An Italian sidesword c.1560 with elaborate gold inlays. The weight listed at only 311.8g must surely be a mistake, considering that the total length is given as 119.5 cm, with a blade length of 102.1cm. The straight quillons are 27.9 cm in width. This is an example of a sidesword with an ambidextrous configuration, and a beautiful blade.

The Royal Armouries

Italian sidesword c.1500. No dimensions are given, but it is hold in the Self Defence Gallery in Leeds. The Self Defence Gallery has an interesting concept behind it, as it showcases police gear, makeshift weapons confiscated by law enforcement and antique swords used for self-defence in the period. Some people (and I’m including myself in this category) may understand the idea behind this exhibit, while hating seeing the corroded remains of a Bolognese sidesword next to kitchen knives and other blades used in present day acts of violence. I prefer my violence to be historical in nature. I am including some photos I took personally, showcasing the same piece next to a small buckler (the 23cm or 9 inches variety). Shadows, reflections, glares, and seams in the glass panels be damn.

While this piece shows substantial signs of damage, it still displays a beautifully shaped hexagonal blade with a classical Milanese style ricasso attached to a simple but elegant crossguard. The quillon block is subdued and without extended langets, the S-shaped quillons end in a ribbon roll, and the finger rings end in finials (similar to what is seen on the modern Albion’s Machiavelli sharp sword). Interestingly, the spheroid pommel has the sides flattened, again, showcasing the intent to have it rest in the palm of the hand. As a last thought, I think this sword would make for an excellent reproduction candidate for the modern sharp and trainer market.

Some Final Thoughts

Looking for that ideal Bolognese sidesword, we find a hexagonal blade with a Milanese type ricasso, or a diamond profile blade that widens after the ricasso. The typical blade is longer than the 90cm we expected, but also narrower than the 3.5cm (or even 4cm) we expected as well. The grip needs to be small, about 8cm, and the pommel must accommodate for it to rest at the base of the palm. Going for straight quillons and a bar guard construction is appropriate, but an S-shape quillons with a ribbed leaf motif results in that perfect look I was looking for.

Very nice - and I 98% agree with your top choice as the best sidesword model. My single addition to your choice would be to add a connecting section on the inside of the fore ring like the one on the Albion Marozzo (https://albion-swords.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/albion_marozzo_practice_sword_9824001405_o-1-1024x767.jpg) - or maybe a swept-forward design.)

Interestingly, I've now seen four hilts and pommels of that EXACT design! You have two on your post (with the same word etched into the blade of both, in fact) and Czerny's auctioned off two others from the exact mold/maker - one with an iron/steel handle and a diamond cross-section blade, and another with a longer thinner blade. I've never seen the exact same hilt and pommel replicated like that except for some of the "Munich town guard" swords, and that other set of German rapiers that were made in batches.

So Czerny's has auctioned off three swords with the exact same hilt and pommel! Or at least made from the same mold. That's fascinating.

Awesome article, thank you!