Depictions of Sideswords and Rapiers

as illustrated in Italian manuscripts, and in some German ones

I am interested in seeing how sideswords and rapiers are depicted in old manuscripts. Ignoring that rapiers mentioned in some places are in fact sideswords, and ignoring that some later sideswords are closer to rapiers than to their predecessors, I want to observe which single-handed sword dominates the fencing culture at a given time and as time progresses. Alternatively, viewing Spada da Lato as a generic Sword by the Side category, one that contains all these specific sword types, then we are just viewing the natural development of the sword as the art of fencing evolves.

In my opinion, fencing is what separates swords between self-defence items of fashion for everyday use, and tools of war to be carried onto the field of battle or in a militia context. Yes, the two are intertwined, sometimes more and sometimes less, and they do borrow from each other, but a certain separation always existed. Do you maximise a sword for a particular fencing tradition, or do you account for practical considerations that result in a stouter blade and a smaller size to facilitate its carry? The answer to this question is what separates the two sword philosophies.

I am looking at manuscripts since I am interested here in fencing swords and the link with their traditions, but even so there are a few caveats to consider:

Not all fencing masters had a say in the preparation of the illustrations. But from this perspective, we can still interpret the depictions of the swords as being the views of the laypeople of those times.

There are instances where we can see an adaptation of the same work to the expectations of different markets. This shows that, while we can decide on an ideal sword for a given tradition, and I’ll argue elsewhere that this is an important exercise to perform, this is arbitrary and depends in part on our expectation for that tradition to begin with.

Another caveat is that, just like in the present, training swords with narrower blades existed. In this case, I am using the depiction of injuries to tell me if a simple sword is supposed to be a trainer (spada da gioco) or a sharp sword (spada da filo). When unclear, I will assume they are depictions of sharp swords, as that makes more sense to me from the marketing perspective of a fencing book.

To get a better idea of the timeline, I will go in the order of the publication of the works, with a notable exception for a posthumous publication. A quick look at the German traditions is separated in its own section at the end.

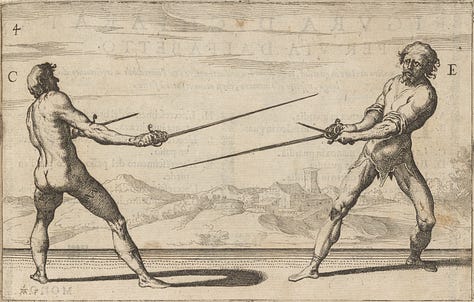

Antonio Manciolino

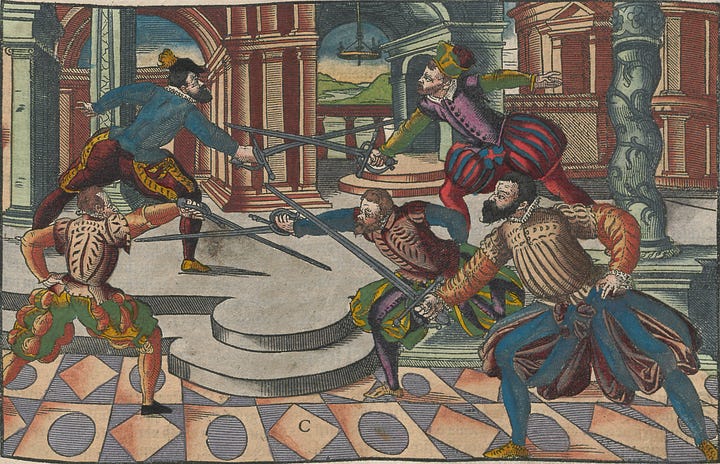

Opera Nova (1531)

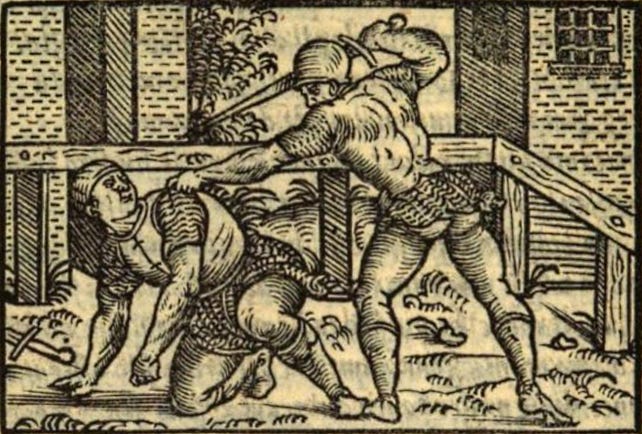

We know that the few images present are generic placements with no particular connection to the text or the Bolognese sidesword system. However, they do show the general use of swords outside the emerging fencing traditions of those times. Viewing Manciolino’s work as being the first Bolognese manuscript, we can see these illustrations as being relevant to the class of swords that preceded sideswords. We see that the swords by the side are falchions (stortas in Italian) or simple hilted swords with blades that have a strong acute point profile (stocco blades in Italian). I like to denote them as field-swords, basically, the infantry swords that soldiers or militiamen would take with them as side weapons. They do tend to have sturdier and shorter blades than later sideswords, and they didn’t evolve as a result of a fencing tradition.

I like to imagine that we are in the realm of militias, with field-swords that just start to morph into sideswords. In a way, I do not view this through the text of Manciolino’s Opera Nova, but I see it as everything that came before him. And if Manciolino disagrees with me, I say he should have added proper illustrations to his manuscript!

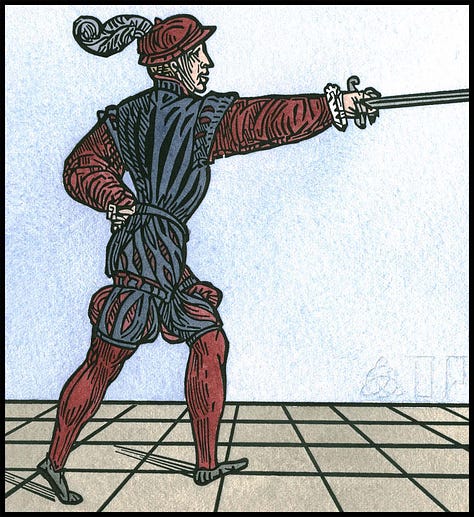

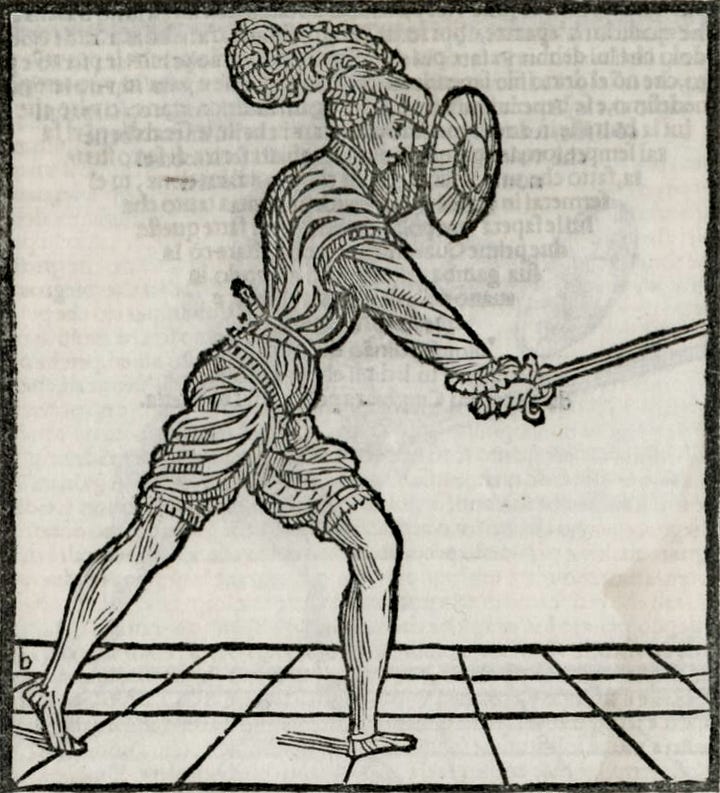

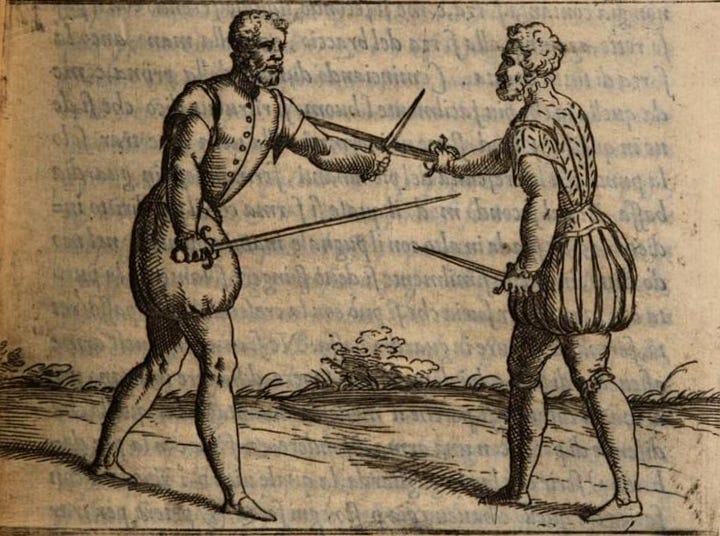

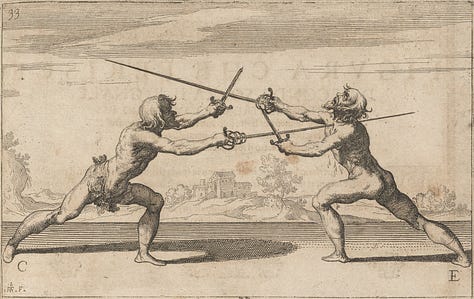

Achille Marozzo

Opera Nova (1536)

This important work for the Bolognese sidesword system showcases the archetypical Bolognese sideswords. We see knucklebows, but the majority of examples don’t have them. We see S-shape quillons out of the plane of the blade dominating over straight crossguards. With extremely few exceptions, we see finger-rings and side-port rings being present. Interestingly, the most displayed pommel seems to be of a bulb type, one with a cylindrical symmetry around the grip, rather than a wheel-type disk pommel. Also, the blades look wide, but not too wide. And they looks long, but not too long. From the stances and the overall look, we see an emphasis on the cut.

These are the swords that most people will think of when we say sideswords. While spada da lato translates as sidesword, and while this can and is also used as a generic category in the Italian language context, the term sidesword is intrinsically connected to the Bolognese fencing tradition. I would prefer to label this sword type as a sidesword and refer to the generic category via the “sword by the side” translation (which includes sideswords, rapiers and maybe more).

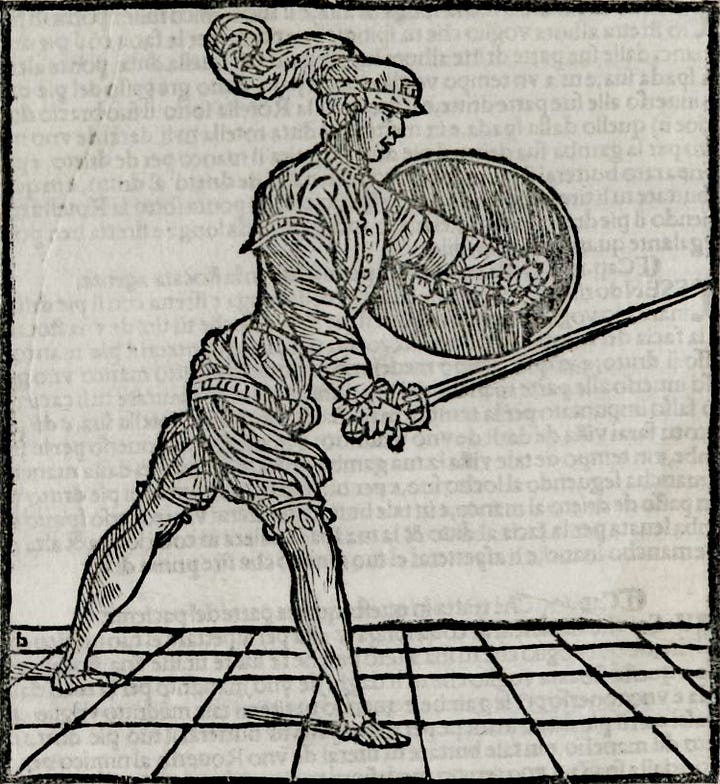

Angelo Viggiani dal Montone

Lo Schermo (1575) - posthumous following his death in 1552

While this manuscript was published much later, we know that the work was done before 1552, so I am using this year to place it in the period. However, a bit of care needs to be considered, since the sideswords depicted in the illustrations may have been a product of the publication process and not of Viggiani‘s intent.

We do see more elaborate hilts, ones with more side-sweeps, and we do see blades of different styles being present. We also see broader blades that are better optimise for the cut, and we see longer, thinner blades that look to be focused on the thrust.

However, the stances are still quite cut-centric in my opinion, so it’s safe to assume that so were the swords for the most part. Notably, we see a sword being held in a handshake grip, so all four fingers are on the grip, which is a more German approach to sideswords. But we also see swords being held with the finger over the crossguard. I think that with Viggiani’s work we see swords blending the cut and the thrust traditions, but it’s not clear if this is due to his approach, or due to the year of publication. By the year 1575, the thrust and thrust-centric swords were well established in fencing.

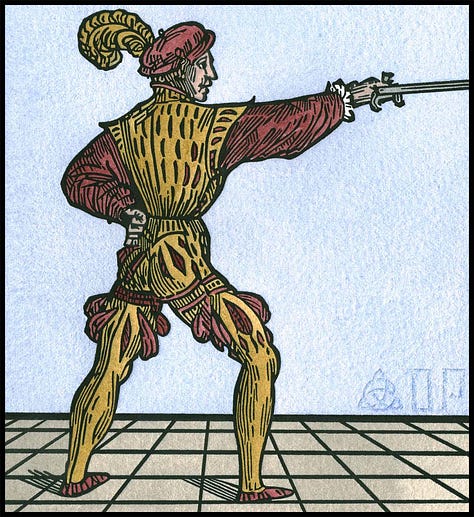

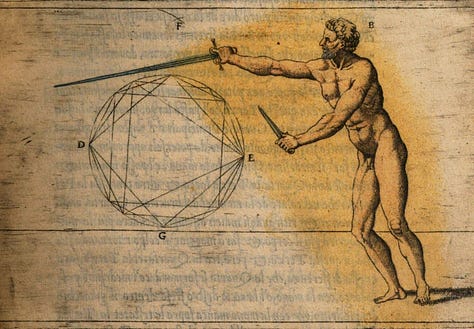

Camillo Agrippa

Trattato di Scientia d'Arme, con vn Dialogo di Filosofia (1553)

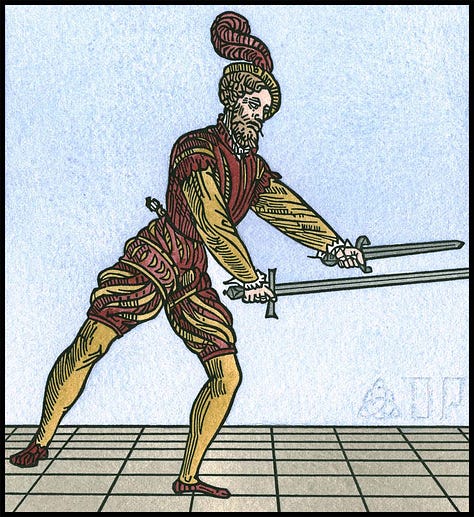

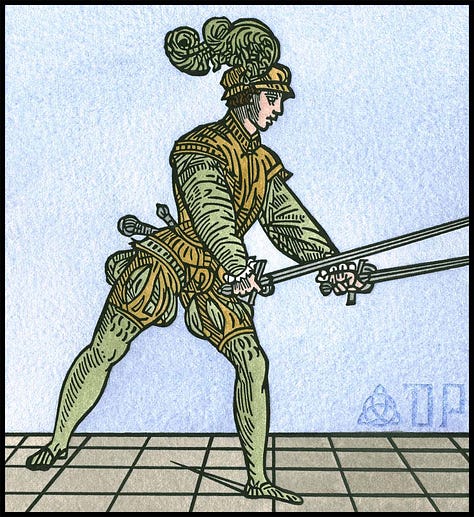

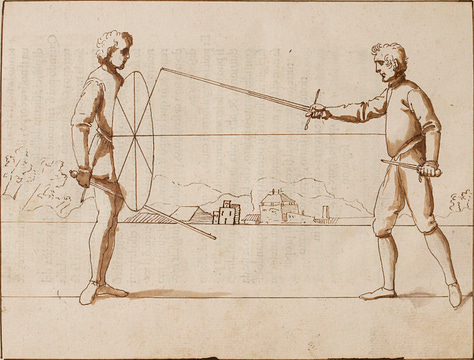

With Agrippa, the idea of the thrust and keeping the point towards the opponent solidified. It is the time when we see sideswords being mounted with slender, longer blades optimised for the thrust. We see this in his depictions of the swords and I will argue that, while these are not rapiers, they are not sideswords either. I would prefer to label them as streak-swords or at least streak-sidesword (incorporating a possible translation for the Italian term striscia into the name) to separate them from sideswords that came before. Notably, the hand grip terminates at the pommel, hinting at swords with small grips.

From the front and back copperplates, which show Agrippa in the company or others, we see that he is depicted with a very simple sword. One sword is with and one is without a knucklebow, but both swords have long and narrow blades.

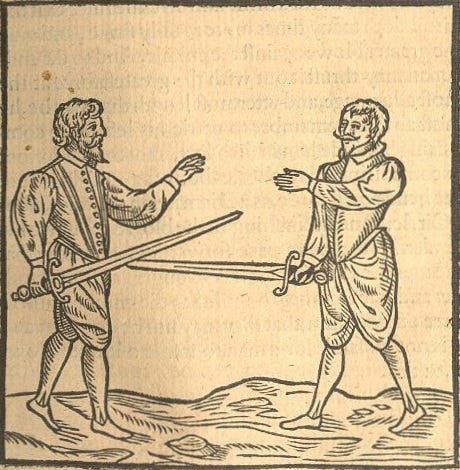

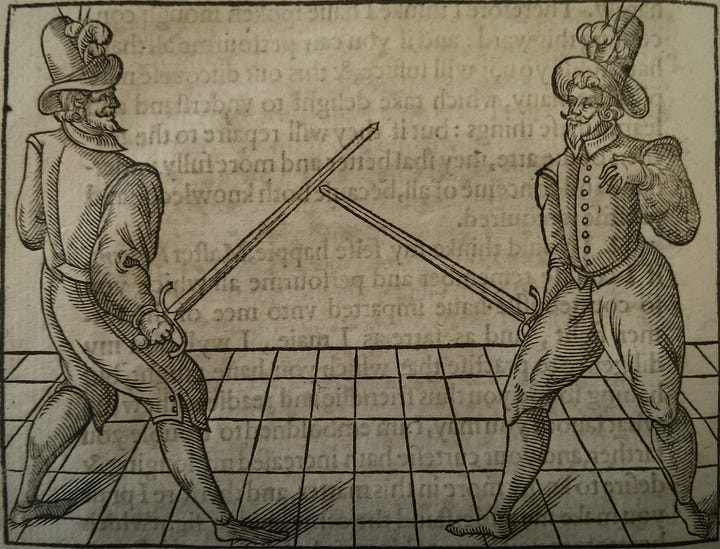

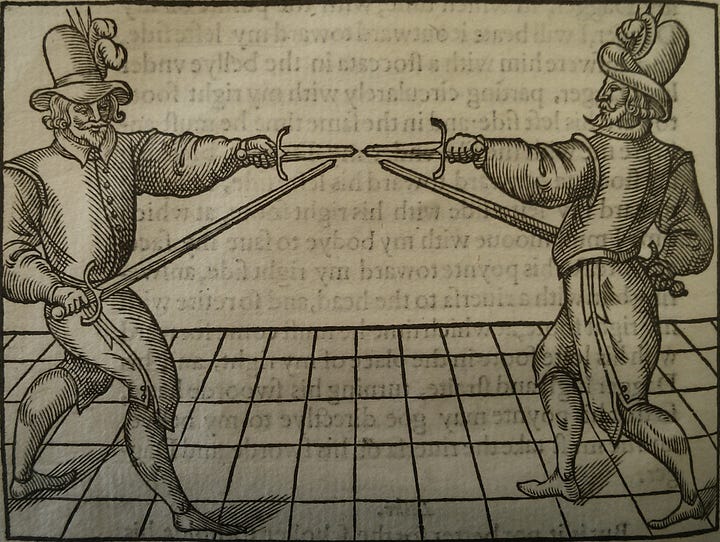

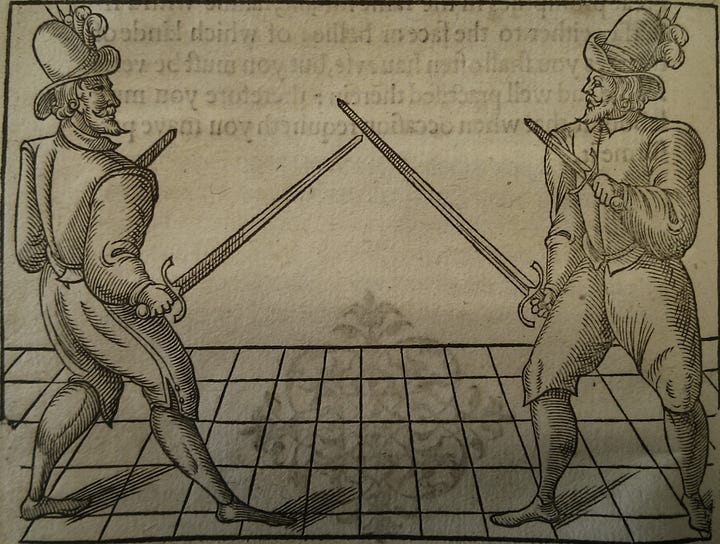

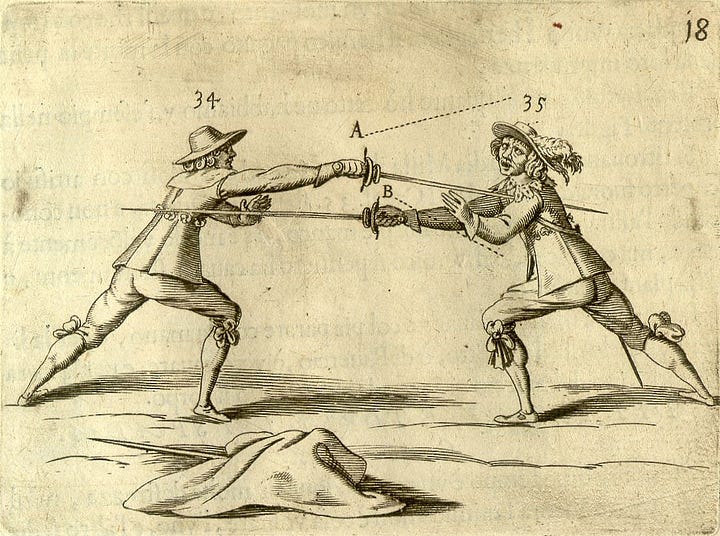

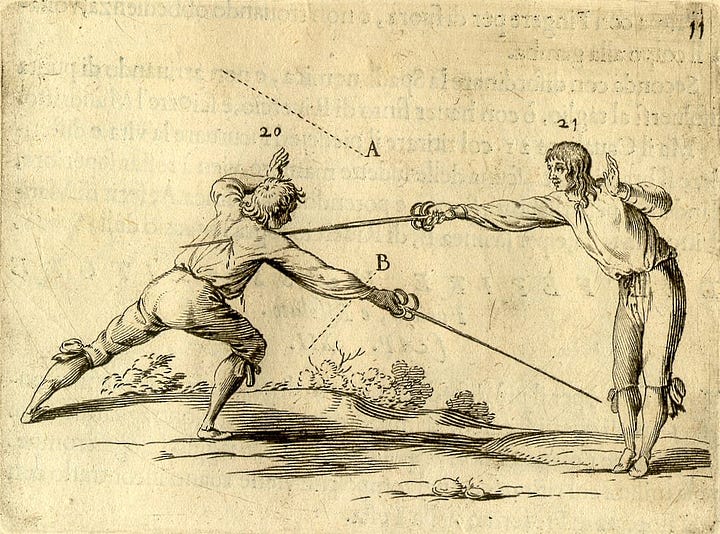

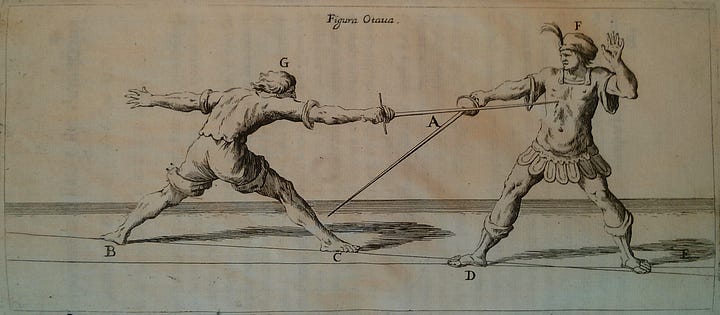

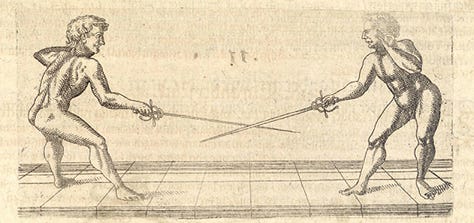

Giacomo di Grassi

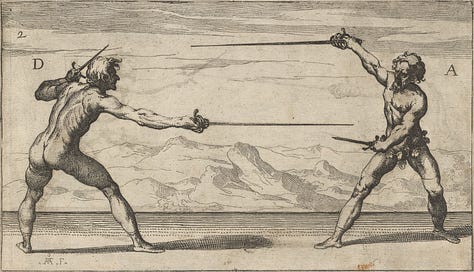

Ragione di Adoprar Sicuramente l'Arme (1570)

It’s interesting that while in his portrait illustration we see a complex-hilt sword laying on the floor (a sidesword, or even a basket-hilt sword), he is shown to have a simple sword by his side, one with a long and narrow blade. The same argument, as in the case of Agrippa, can be made for the classification of the sword.

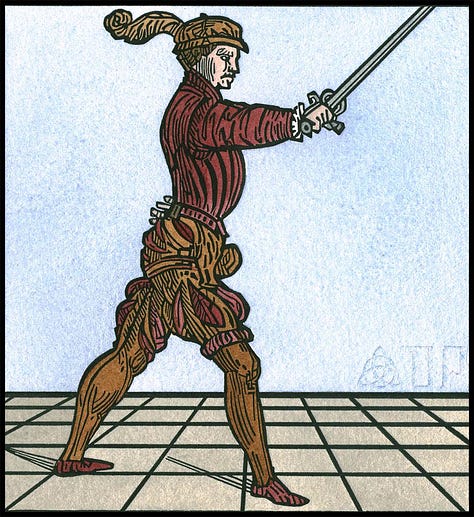

The swords depicted show some variations for the crossguards, but they all show long and narrow blades in stances that promote keeping the point toward the opponent. The finger-rings, S-shape crossguards and some knucklebows are hilt elements accompanied by pommels that start immediately at the base of the hand. Again, we have a short grip and long narrow blades.

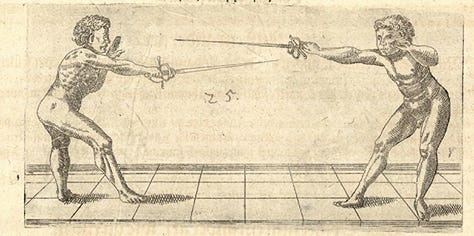

His True Arte of Defence (1594)

This English translation of di Grassi’s work shows blades that are much broader in profile. I believe this is an adaptation for the English market, where cut-focused swords never got out of style.

The crucial difference in the depiction of swords in the English translation compared to the Italian work is the absence of fingering the crossguard. To me, this makes it closer to the “English shortsword” of George Silver as presented in his Paradoxes of Defence (1599).

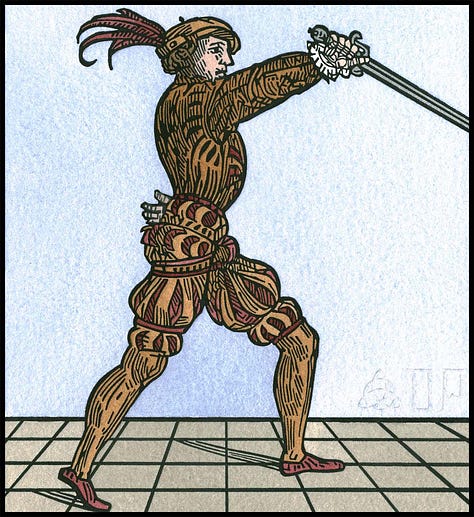

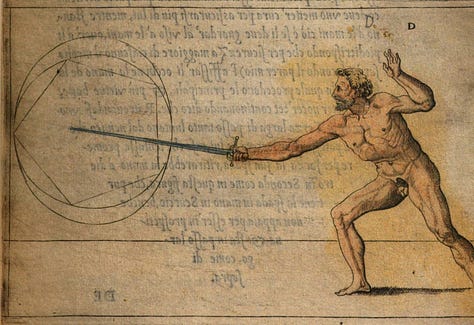

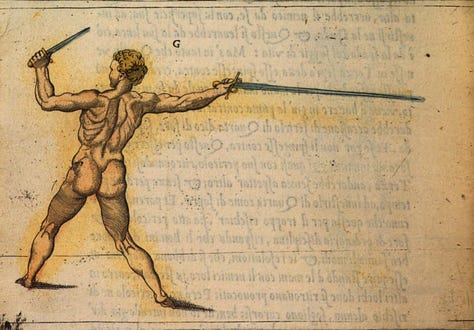

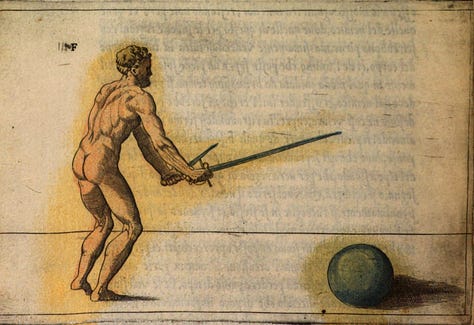

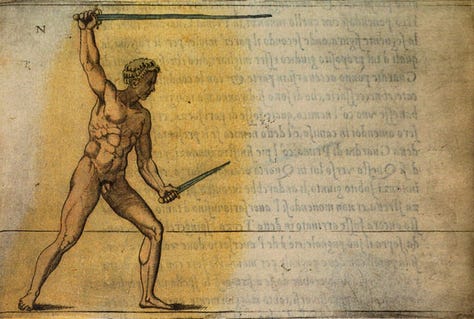

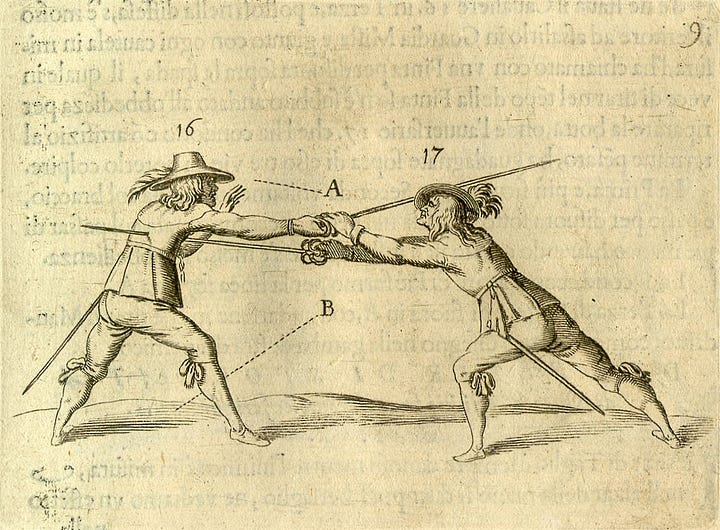

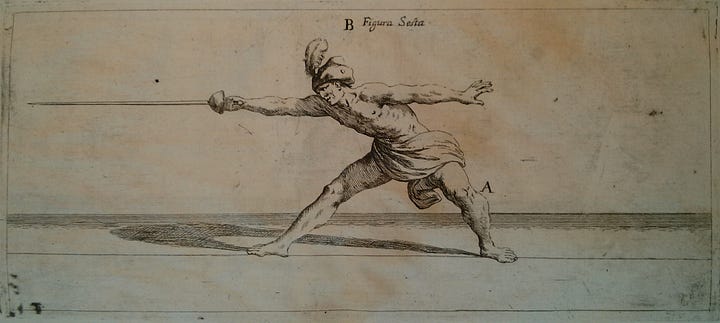

Federico Ghisliero

Regole di Molti Cavagliereschi Essercitii (1587)

A Bolognese soldier and a fencer in the style of Agrippa. The swords depicted in his work have crossguards with very long quillons. While still mounted on simple sword hilts, we see long blades that would rival ones seen later on rapiers, with the quillon block reaching the navel of the swordsman when having the sword by his side. As a side note, the style used for the illustrations is beautiful and expressive.

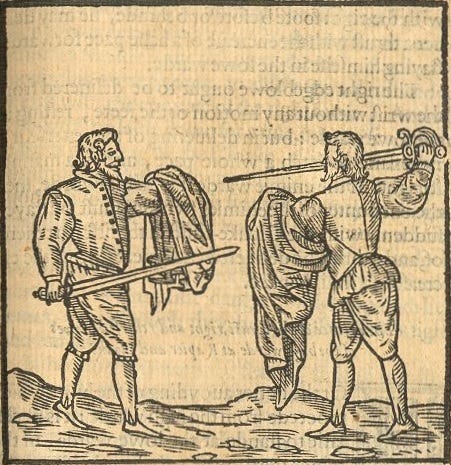

Vincentio Saviolo

His Practice, in Two Books (1595)

Another Italian master who published his work for the English market. While we are told that he taught Italian and Spanish rapier systems, we see the depiction of broad-bladed swords in his book. Moreover, we don’t see the finger over the crossguard in the depiction of the grips, an absence that makes it consistent with the use of swords in England.

Camillo Palladini

Discorso sopra l'arte della scherma (prepared ca.1600; but not published)

We are told that this manuscript was prepared around the 1600s. However, it was never published until a few years ago. I’ll resume to posting a single image from it for the sake of completeness. The swords look to be in the style of Agrippa, maybe longer blades, but I wouldn’t call them rapiers.

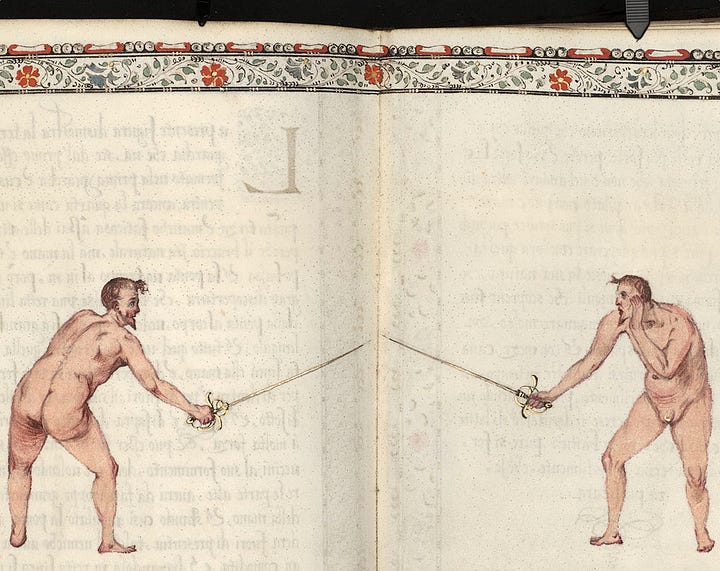

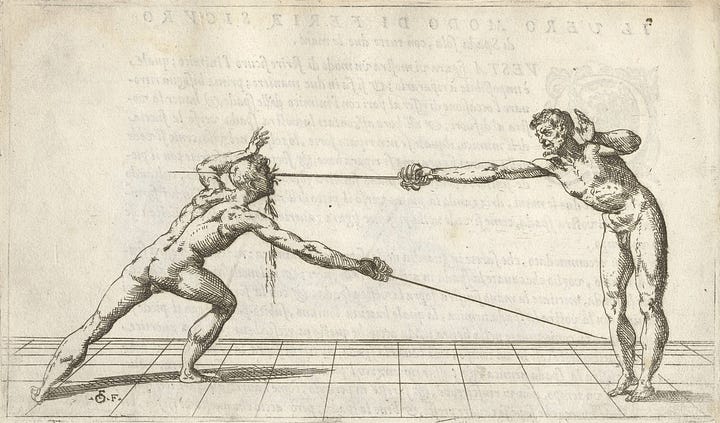

Salvator Fabris

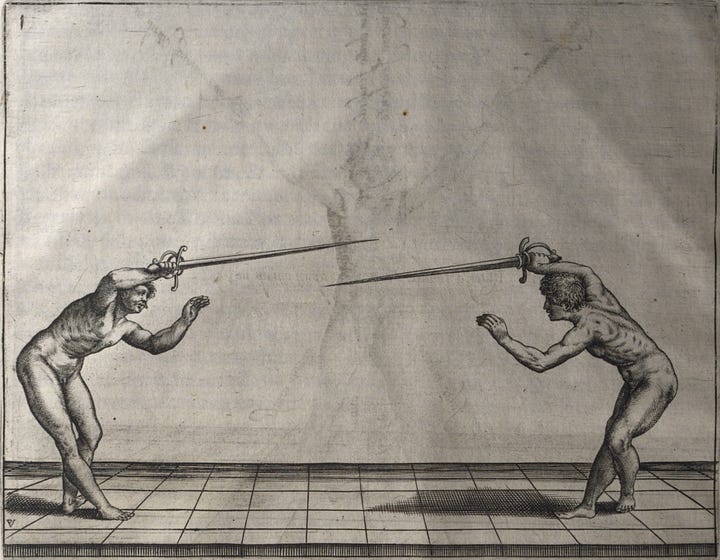

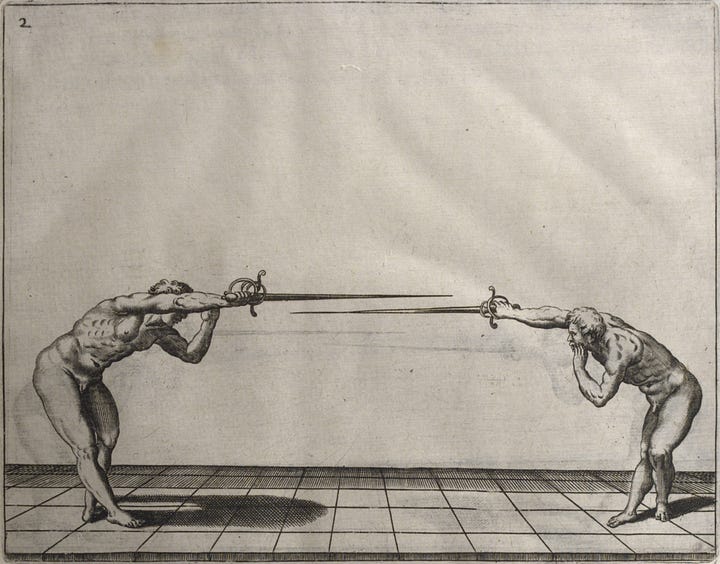

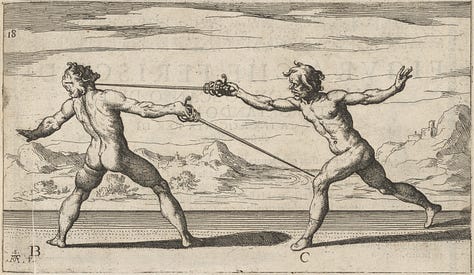

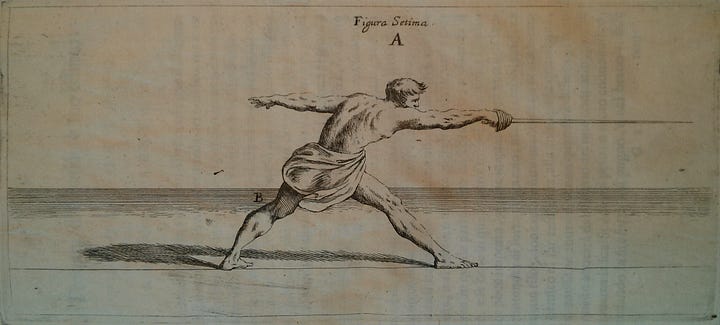

Scienza d’Arme (1601-06)

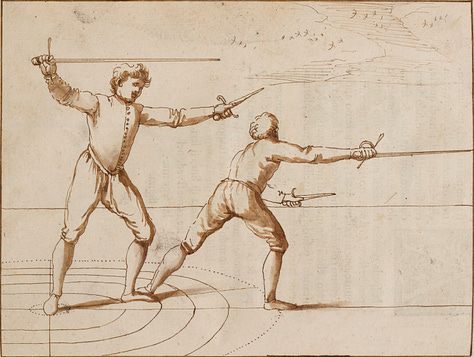

This work shows the first proper representation of a rapier. The blades are long and the hilts are complex. The two or three-ring hilts are shown at times to have closed ports via plates stylised to look like shells. The straight or curved quillons and the presence of knucklebows look familiar to what we associate with rapiers in the present day. The pommels look to be olive-shaped.

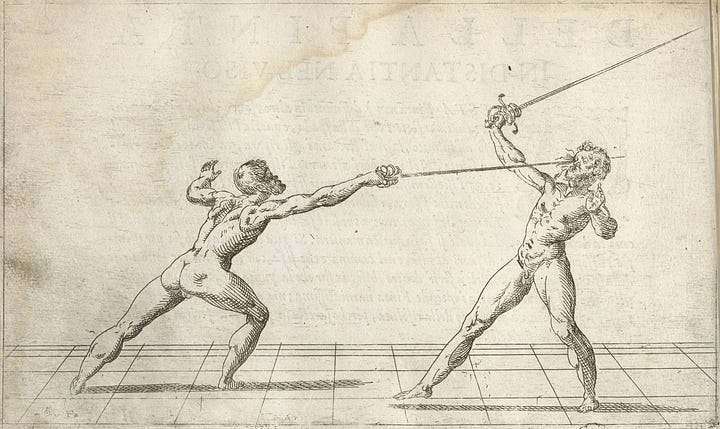

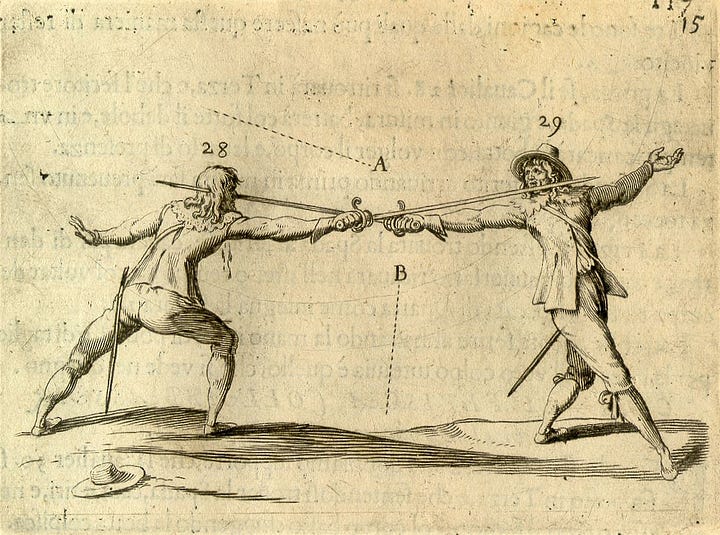

Nicoletto Giganti

Scola, Overo Teatro (1606)

The rapiers shown in the work of Giganti are very similar to the ones shown in the work of Fabris. We do see a higher preference for left-right symmetric hilt designs, but for the most part, I consider them to have the same look.

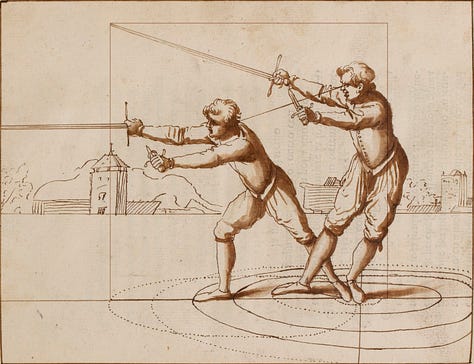

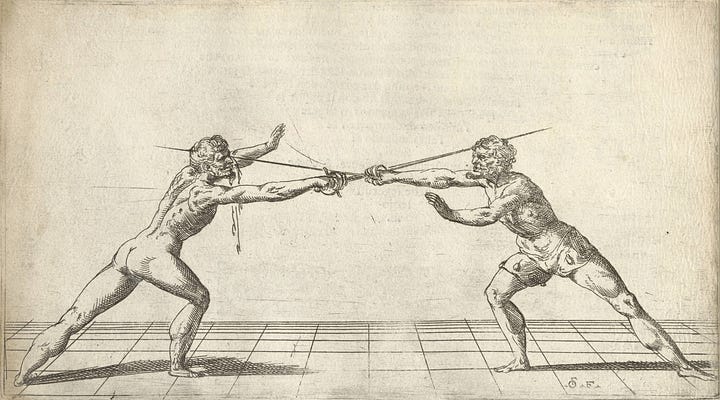

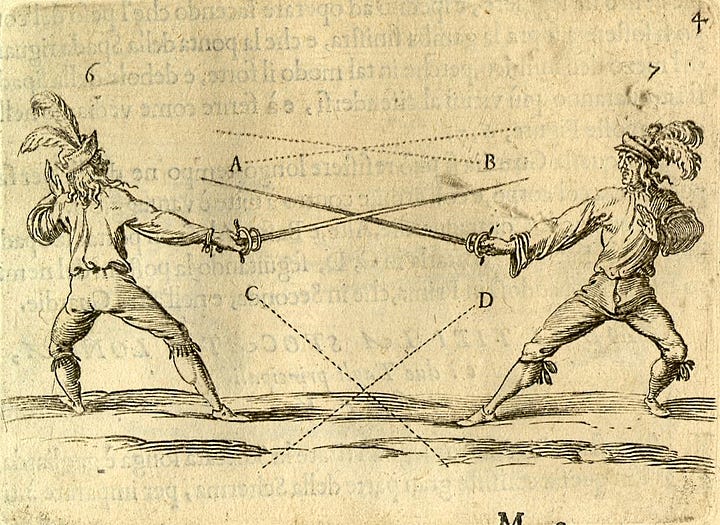

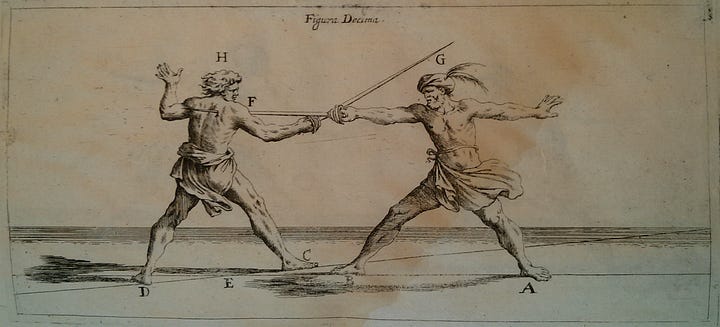

Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli

Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (1610)

The long rapiers depicted in the work of Capoferro have some of the most intriguing hilt designs that I know of. To this day I am fascinated by the sweeps displayed, especially when the bottom quillon is absent, yet I don’t actually understand how they are connected. A screw-like hilt design is what comes to mind, but this is speculation.

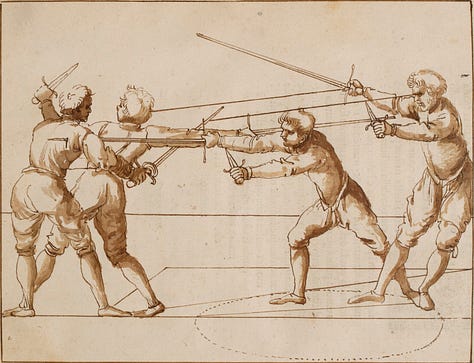

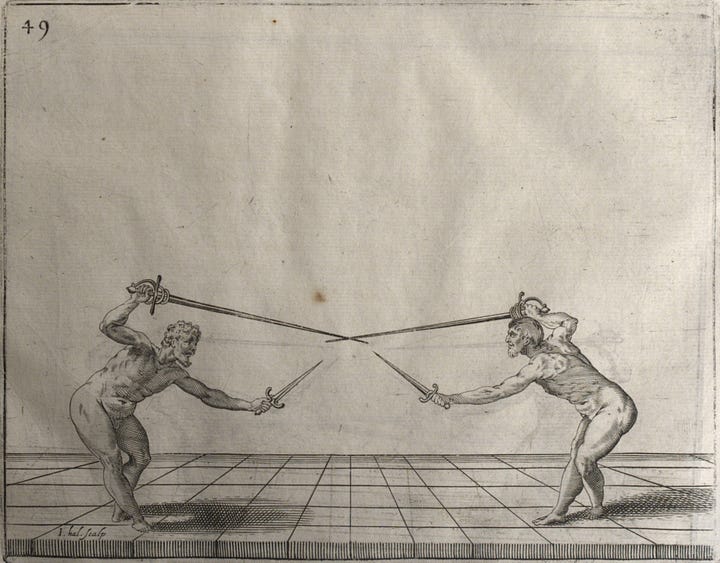

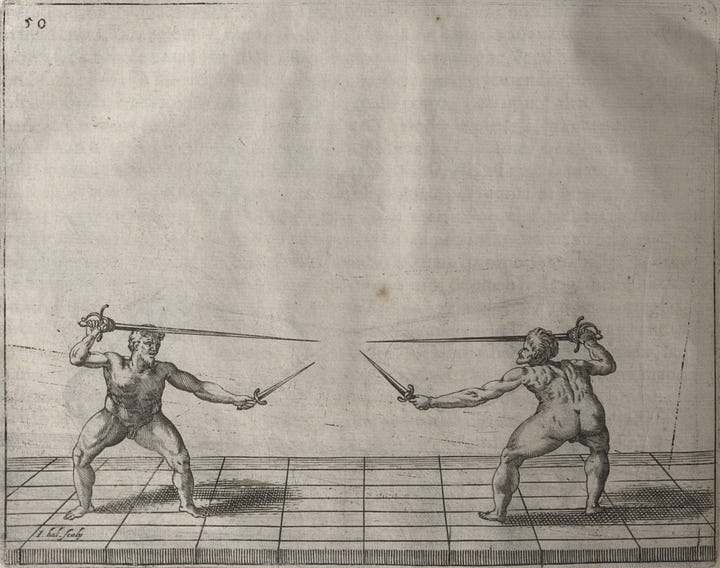

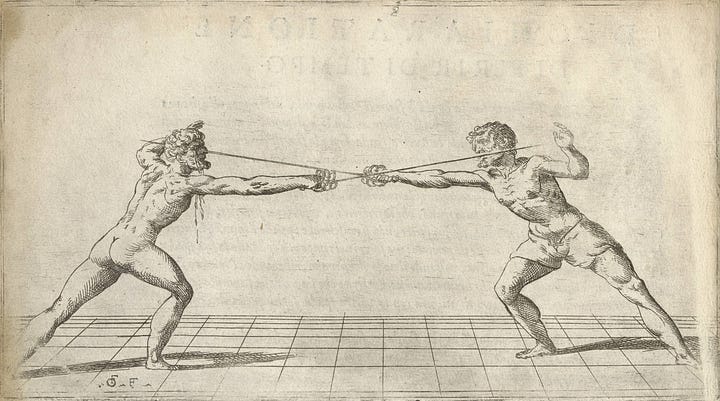

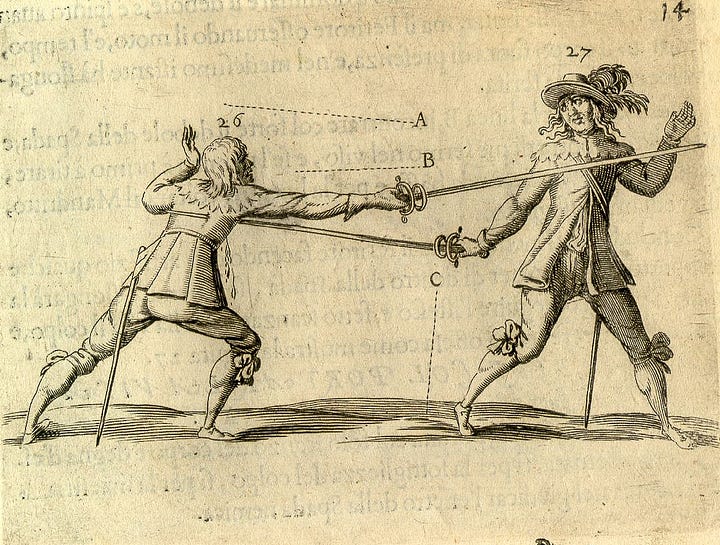

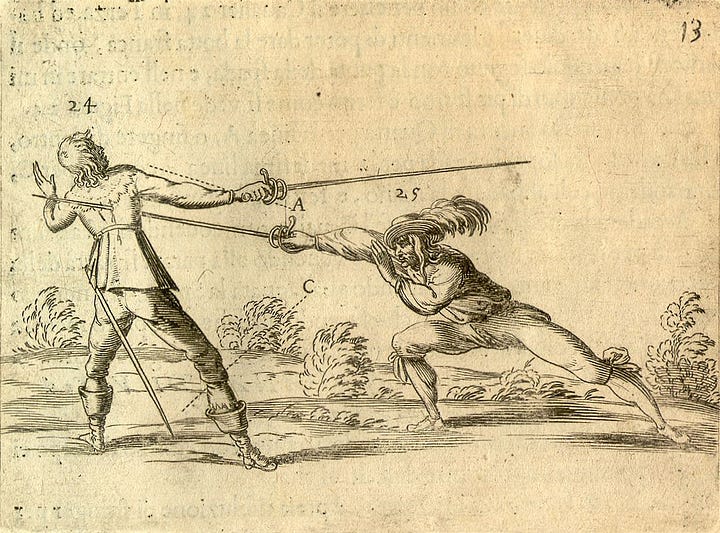

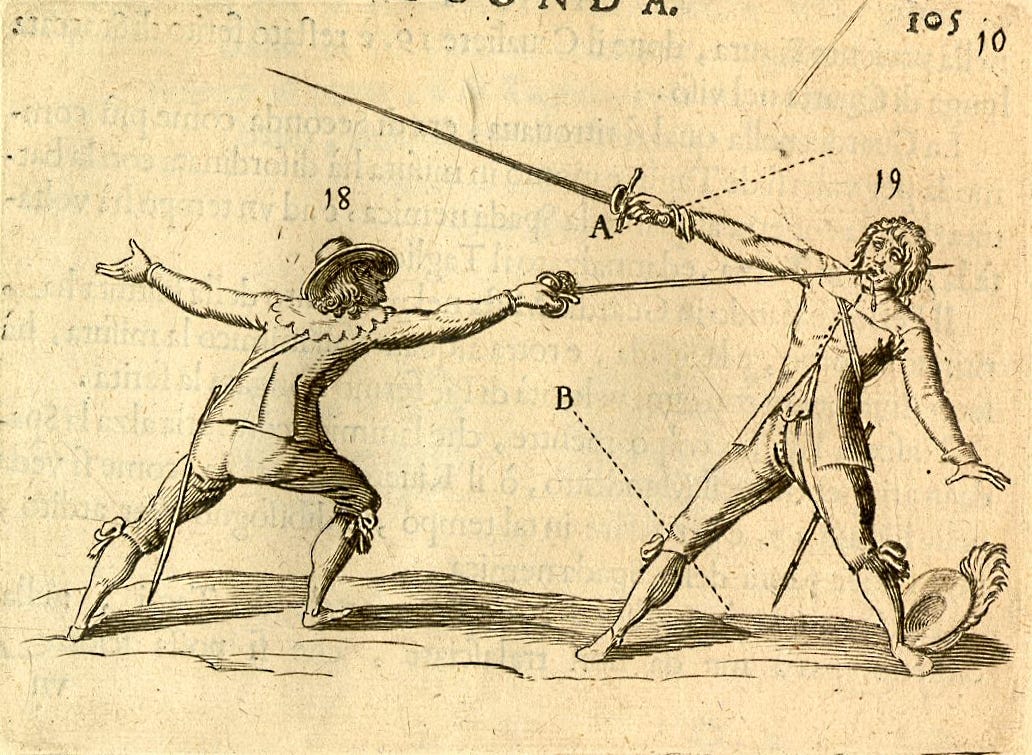

Francesco Fernando Alfieri

La Scherma (1640)

All rapiers in the work of Alfieri are depicted with very long blades. However, the hilt are diverse. We see a two side-ring configuration akin to the Thibault rapier. We see a single ring port at the level of the crossguard. We see a left-right symmetric two side-ring hilt design. And we see a hilt design similar to the one depicted in the work of Capoferro.

Alessandro Senese

Il Vero Maneggio di Spada (1660)

This late Italian fencing master from Bolognia depicts the use of cup-hilt rapiers, or a rapier with a seven-ring style hilt, in his true way of handling the sword. While he is using cup-hilt rapiers, his fencing style is still that of the in-line Italian tradition, from what I can tell. So not all cup-hilts are used for Destreza, just like not all swept-hilts are used for Scherma.

A Bonus Look at German Traditions

The main difference in using a sidesword in the German tradition, which they refer to as a rapier at times, is the placement of the thumb on the blade and the preference for the hand-shake grips. In this aspect, they are closer to the “English Shortsword” of George Silver. They are also more cut-focused, but not as much as the English, in the same way that Italians are more thrust-focused but not as much as the Spanish.

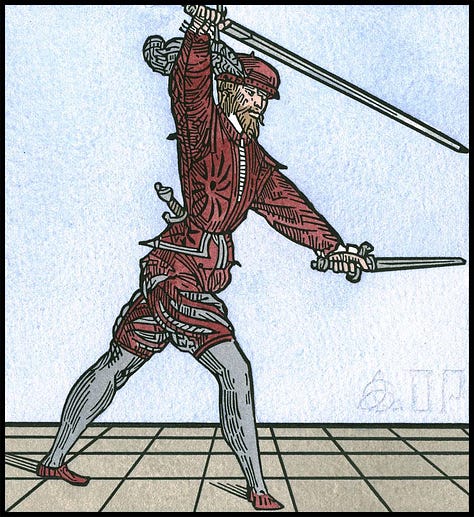

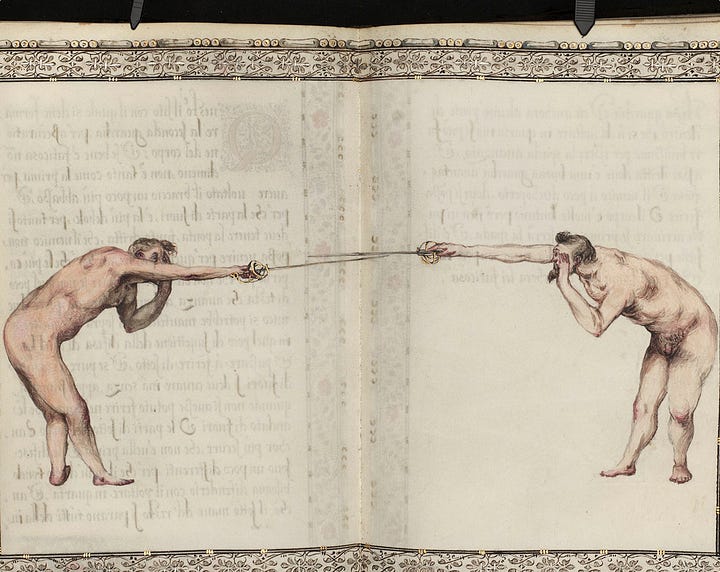

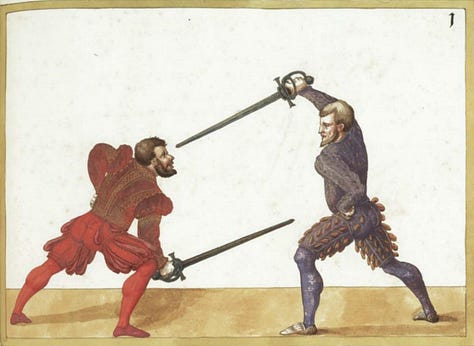

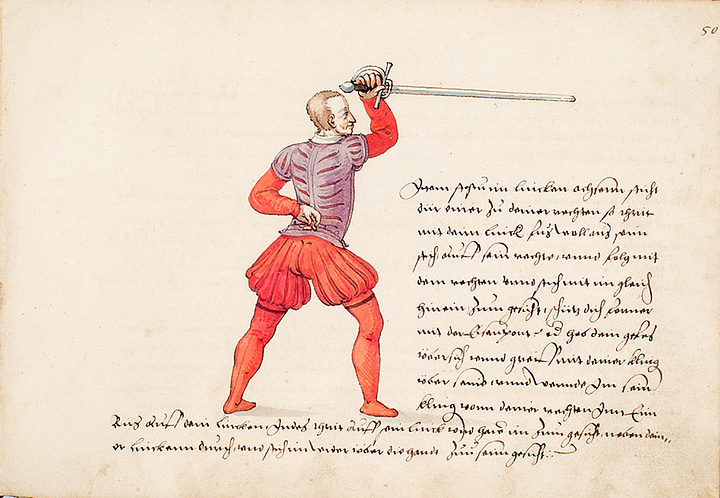

Paulus Hector Mair

MSS Dresd.C.93/C.94 (1540s)

An interesting German sidesword. We see sweeps that protect the outside of the hand, but we also see a finger-ring on the inside of the crossguard. So this is similar to some later German sabres, where one has the extra leverage from fingering the crossguard without actually doing it while maintaining a more hand-shake grip. A very interesting compromise between German and Italian traditions, in my opinion.

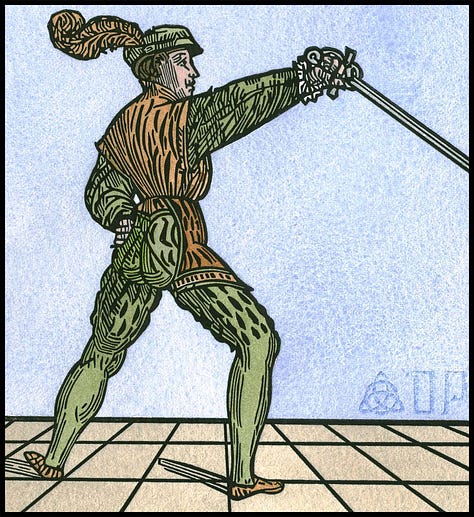

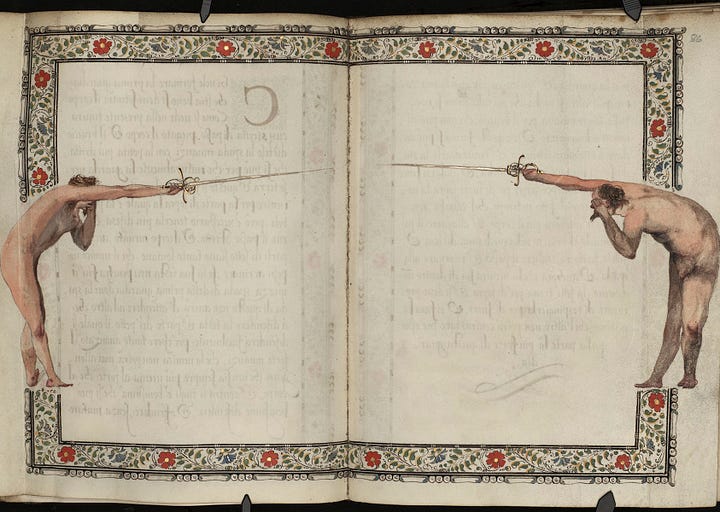

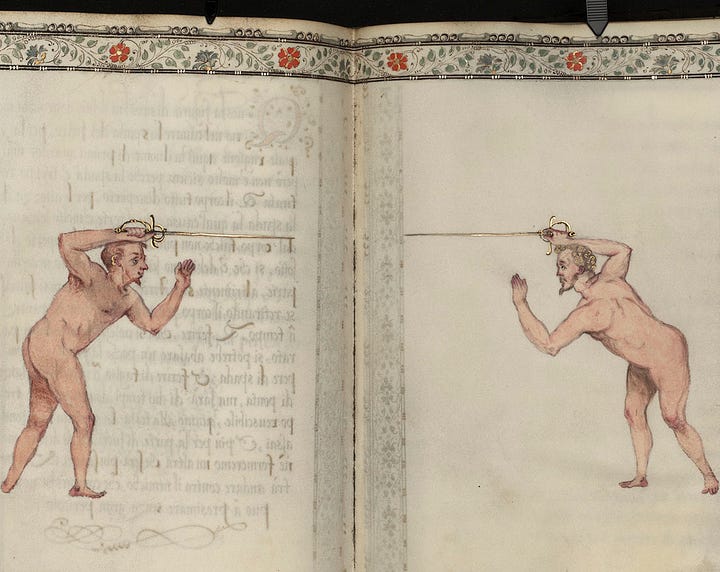

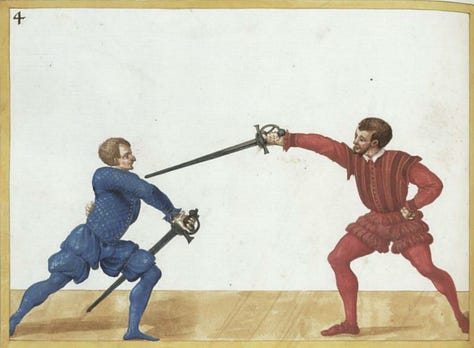

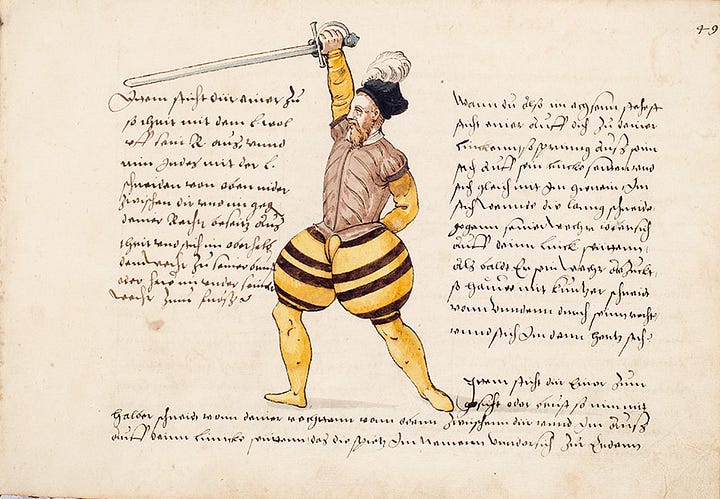

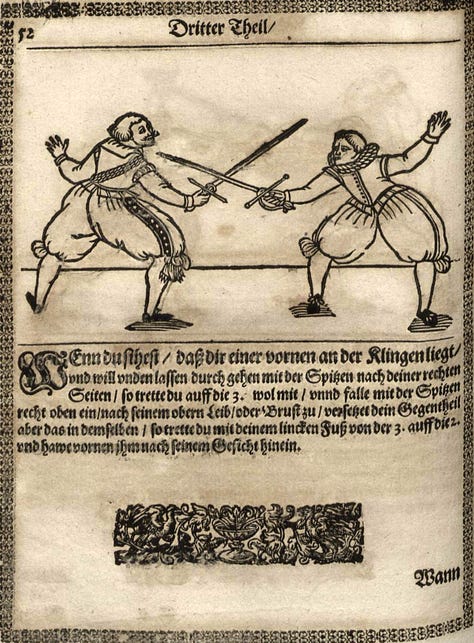

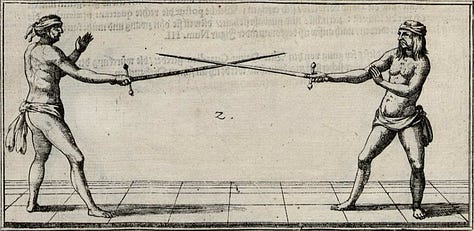

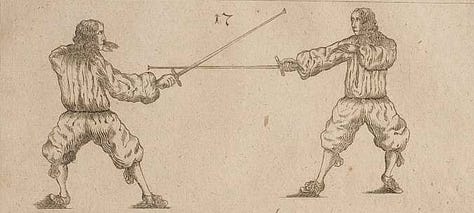

Joachim Meyer

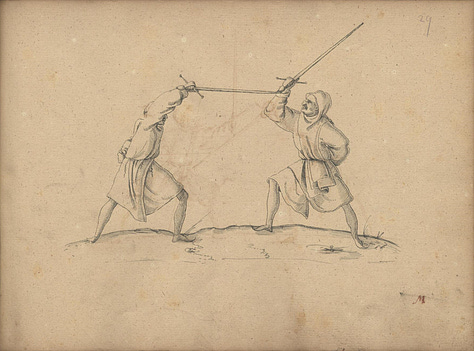

Veldenz Treatise (1561)

A German sidesword where the hand-shake grip is dominant and one cannot finger the crossguard. Moreover, they look like sharp swords and not trainers. This tells us that broadswords and half-basket hilted swords work well with German cut-focused sidesword systems. This is an obvious statement, but one that needs to be made to emphasise that half-basket hilted swords, ones that allow you a greater range of motion compared to a full-basket hilt, can serve the same purpose as a sidesword. While the former swords are closer to sideswords in use than to the latter, they are separated from their Italian counterpart by not being able to finger the crossguard.

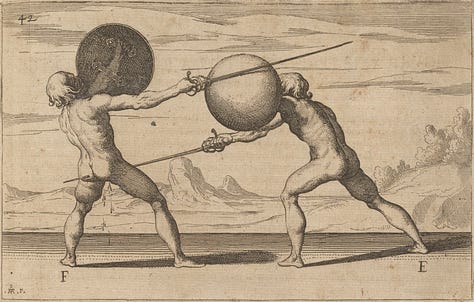

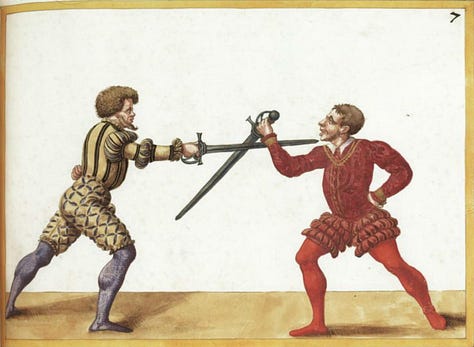

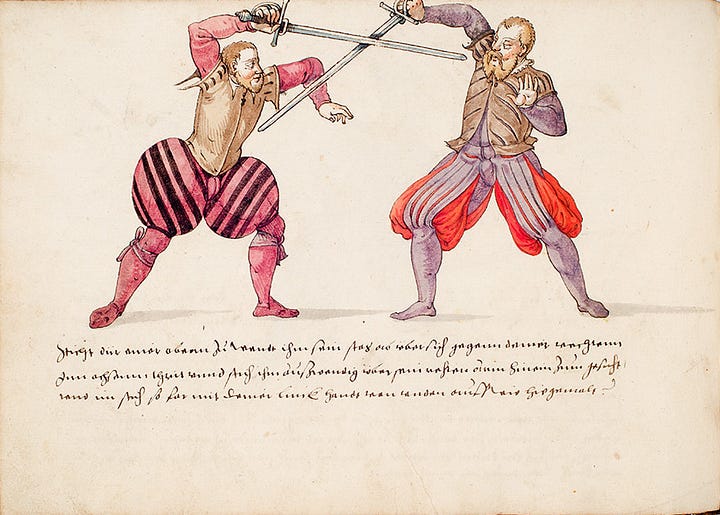

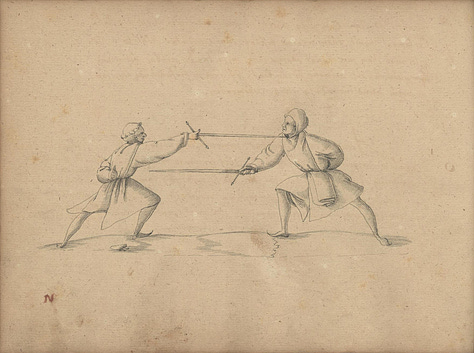

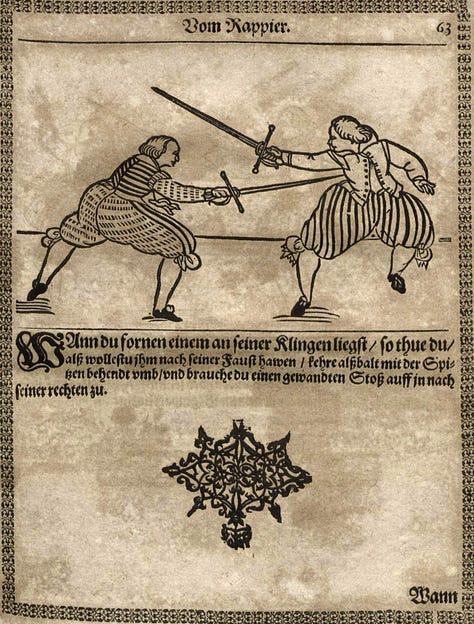

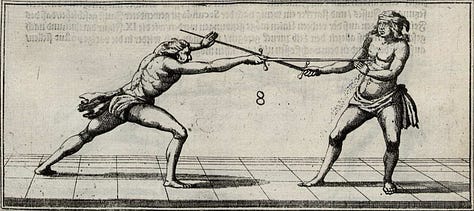

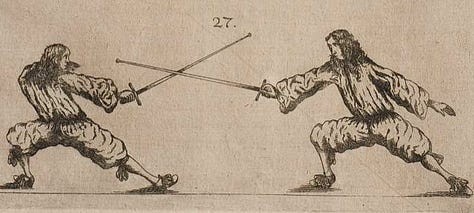

Solms Treatise (1563-8)

In this later treaty, we see a trainer. It is interesting to see a schilt on a single handed sword. The “Meyer rapier” is now iconic in the HEMA community.

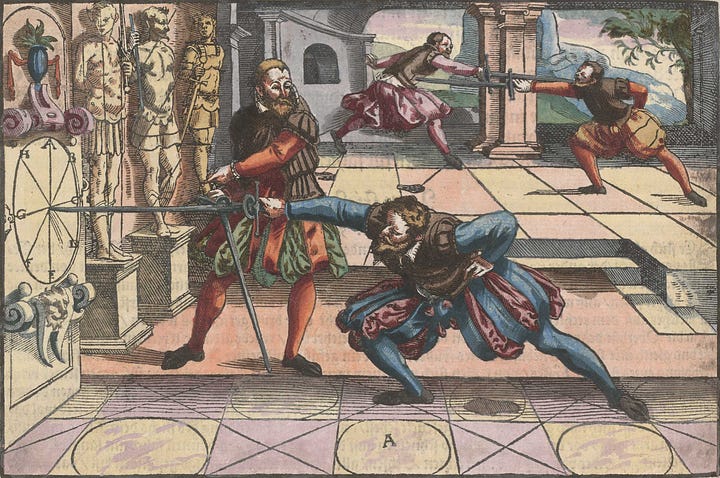

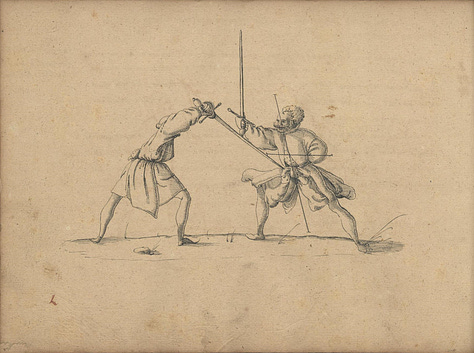

Gründtliche Beschreibung der… Kunst des Fechtens (1570)

In this even later treaty, we see the depiction of the same “Meyer rapier” sidesword trainer. I do find it interesting that in his later years, Mayer preferred to showcase his illustrations in the context of a school rather than as actual combat. It shows a cultural shift in the Germany of those times, in my opinion.

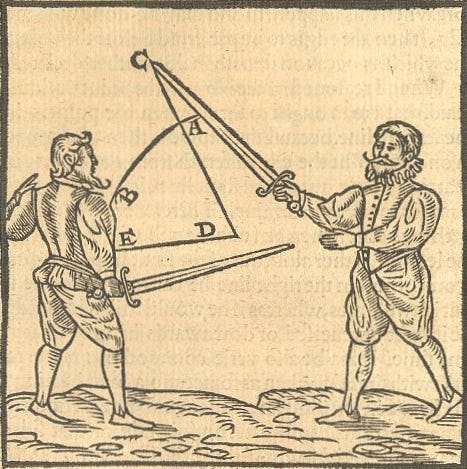

Heinrich von Gunterrodt

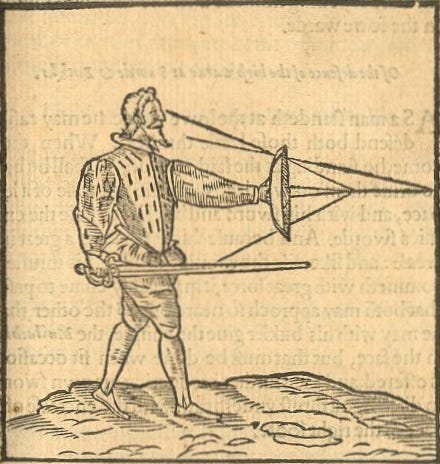

De Veris Principiis Artis Dimicatoriae (1579)

The detailed depiction of the sword shows a wider blade than expected. This might be an artistic choice to save space on the paper, especially when considering the subsequent depiction of a much longer blade in the fencing illustrations. What’s truly fascinating is the thumb protective ring or closed port and the outer sail guard that limits drastically the way this sword can be used. Also, the quillons are quite long.

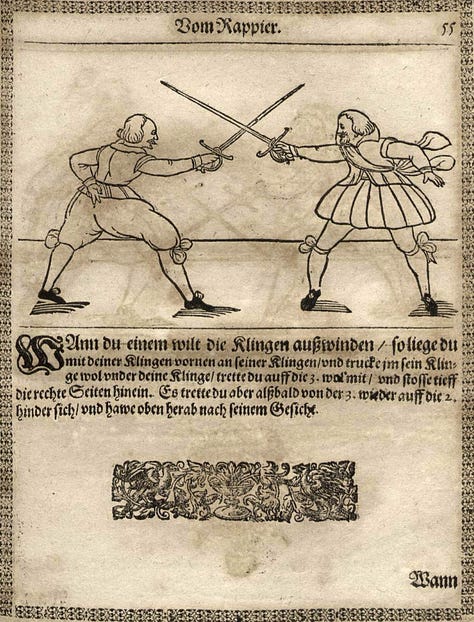

Jakob Sutor von Baden

New Kůnstliches Fechtbuch (1612)

The depiction of the sword shows it to be similar to the one used by Heinrich von Gunterrodt, above. We see the same thumb protective ring, an outer sail-like guard and long quillons. This shows that this type of sword was in use for a few decades.

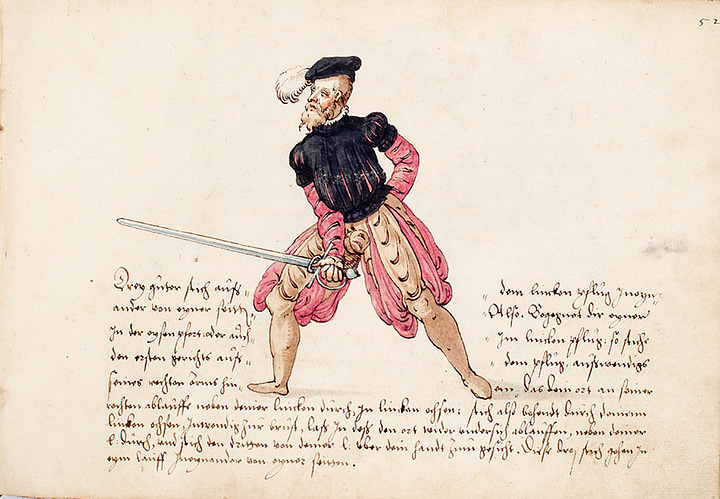

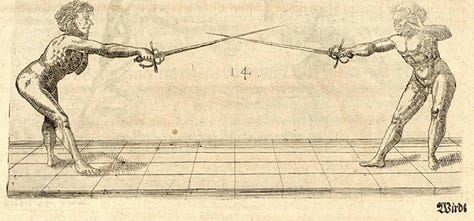

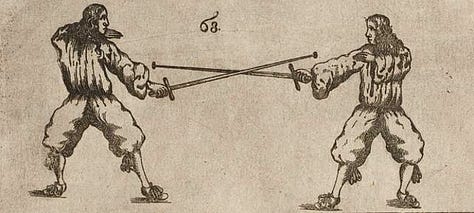

Hans Wilhelm Schöffer von Dietz

Grůndtliche vñ eigentlichte Beschreibung der Fechtkunst (1620)

A three-ring rapier with a left-right symmetric hilt. While I am assuming that the blade is depicted as being shorter than in reality to save space on the paper, the hilt is recognisable and is indeed seen on museum pieces. In the fencing illustrations, we also see a simpler left-right symmetric two side-ring hilt design.

Johann Daniel Lange

Deutliche Erklårung der Fechtkunst (1664)

We see a simple rapier, one with a shallow cup or a dish hilt. However, its use is more in the Italian tradition, and the dish is absent in the fencing illustrations, probably to offer a better view of the hand during its use. We do see that all four fingers are around the grip and the quillon block is pinched, which is more inline with Thibault’s grip for a rapier than the Italian tradition. Indeed, a shallow cup or a dish hilt can prevent fingering the crossguard, so what we see here is the move towards the transitional rapier.

Johann Georg Pascha

MS Dresd.C.13 (1671)

We see the depiction of a training sword, one that shows a clear blunt tip. This is one of the few manuscripts that shows training as a sport rather than a duel. I find the lack of blood and thrusts through the skull to be off-putting and disturbing. Joke aside, I genuinely don’t think that I would have started HEMA if this is how all manuscripts were depicting swords and the art of fencing.

Closing Thoughts

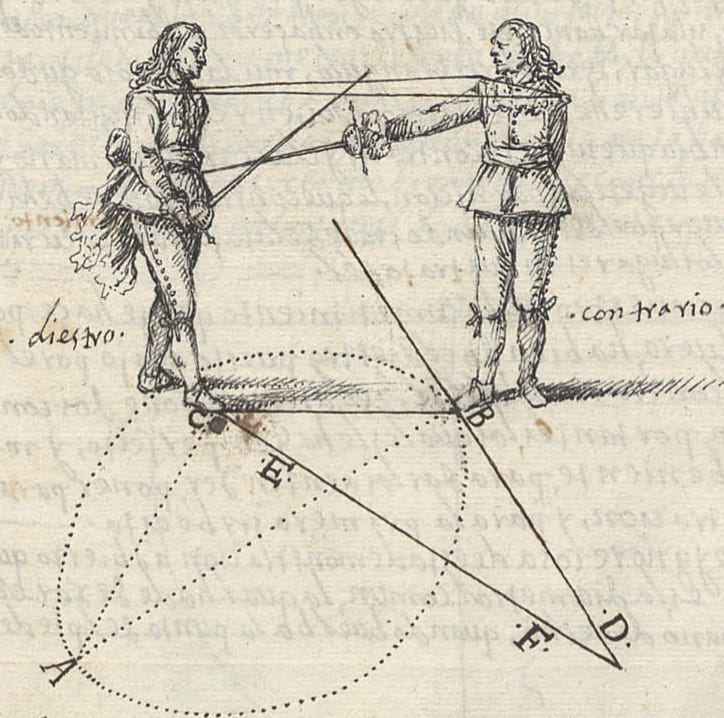

I didn’t want to include manuscripts that appeared after the 1700s. I also left out Spanish, French, Dutch and English masters. So I left out La Verdadera Destreza rapier traditions and masters like Gérard Thibault d'Anvers.

I will however post one image from Gérard Thibault d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée (1630) to showcase the design of the iconic two side-rings and inner-sweeps rapier.

Interesting article, nice to see all the illustrations in one place. Lots to study.