Context

I was reading David Biggs’s post on “What is a rapier, anyway?” and I saw a reference to spada da lato striscia (footnote 7).

The designation striscia sounded familiar to me, but it also sounded like hearing it for the first time. I believe that spada da striscia can be translated as a streak-sword, to denote a sidesword with a long and narrow blade of the type that preceded rapiers. striscia is translated into English as a strip, stripe, or streak. I prefer streak since its verb form refers to moving very fast in a specified direction, which makes sense for a thrust-centric sword and the lunge. But before addressing my speculative labelling in a future post, having had a look at the depictions of sideswords and rapiers as illustrated in Italian manuscripts, I want to see how the present-day Italian language refers to sideswords and rapiers. Maybe I can learn something from this exercise.

I will look at stores that sell mass-produced swords for reenactment as a way to gauge laymen designations, a store that sells HEMA gear for a more informed opinion, and an auction house for a specialised context. Warning, embrace the insanity!

Online Stores and Auctions

La Casa del Recreador

For a reenactment store, they use striscia spagnola in reference to a rapier that they describe as a stocco o (or) striscia. So from the start, we see the interchange between stocco and striscia. Yet for similar rapiers they use spada a striscia and rapier a striscia. Some spada a striscia are described as being spada rapier, and the rapier a striscia is described as spada civile a striscia. The cherry on the cake of confusion is a spada da fanteria (infantry sword) for something that looks like any other rapier sold, but we will leave that one alone. Are you confused? Let’s move on.

Reges Store

From the start of this reenactment and larp store we see the category of interest being labeled as Spade da Lato e (and) Rapier. So we are led to believe that the two are separate. Except that for one stocco and three rapier products, we read their descriptions as replica di (replica of) spada da lato… So far, we see an interchangeable use for spada da lato, striscia, stocco, rapier. Let’s move on.

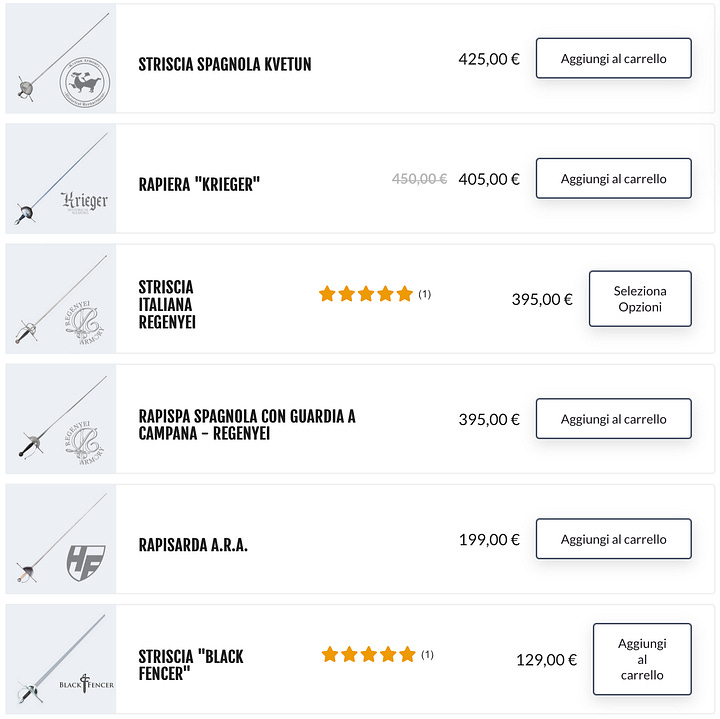

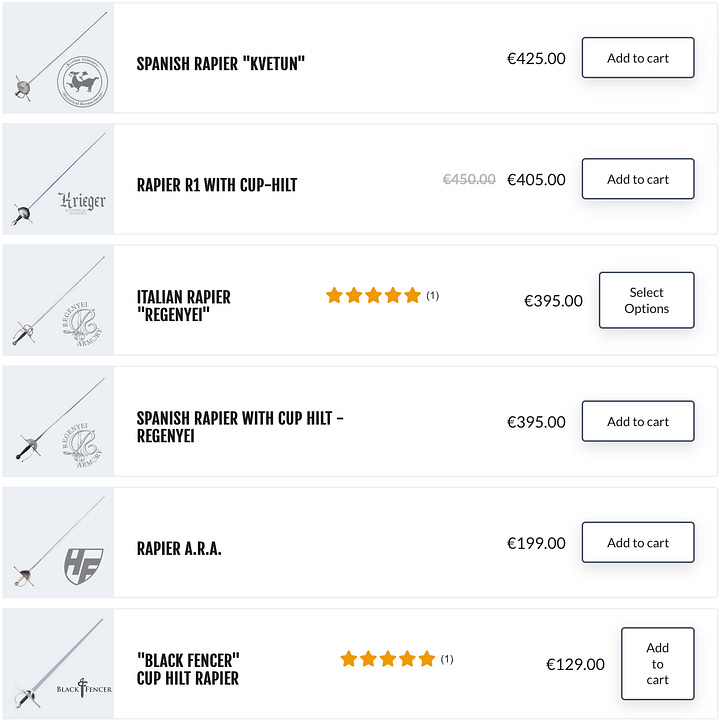

Fait de Armes

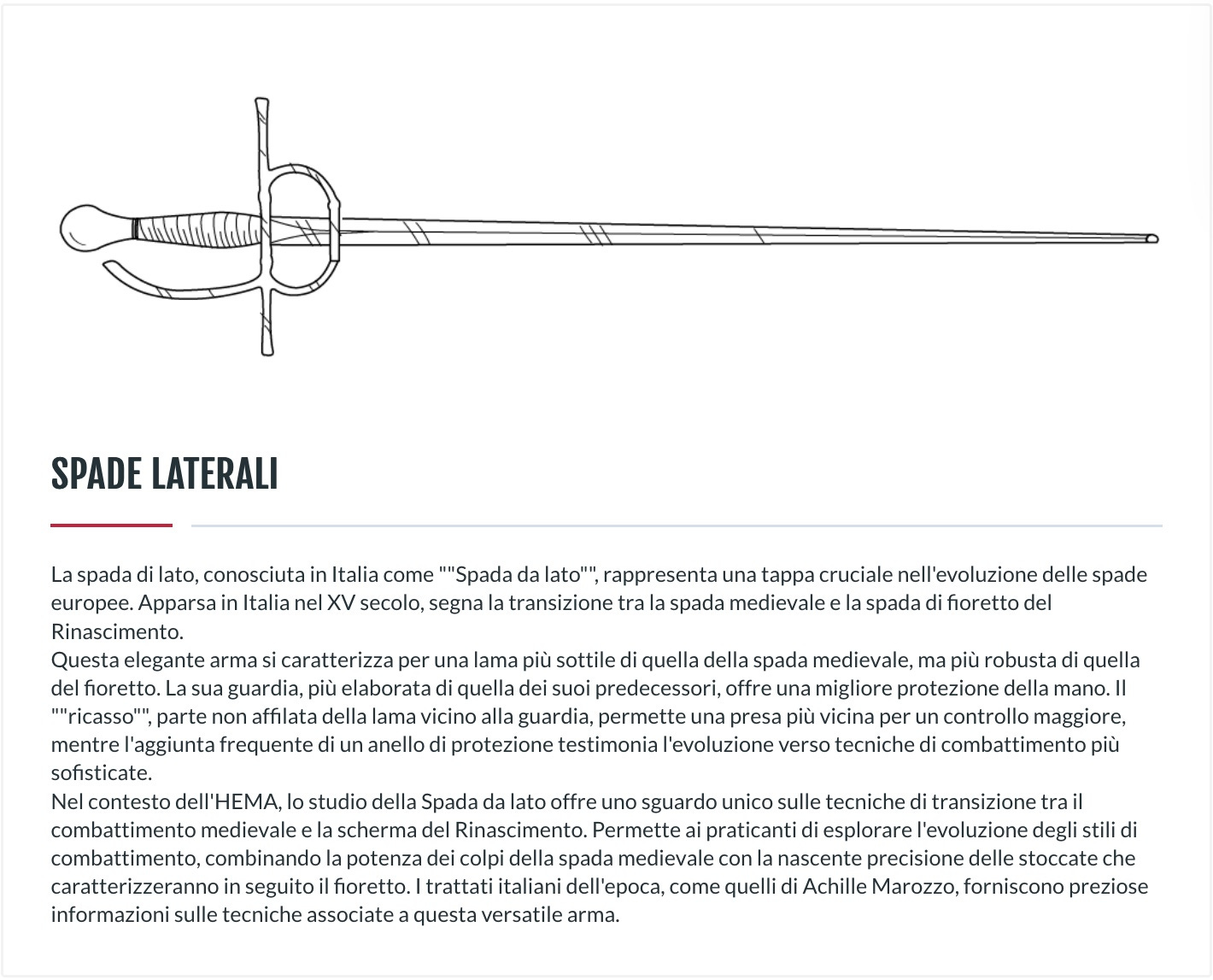

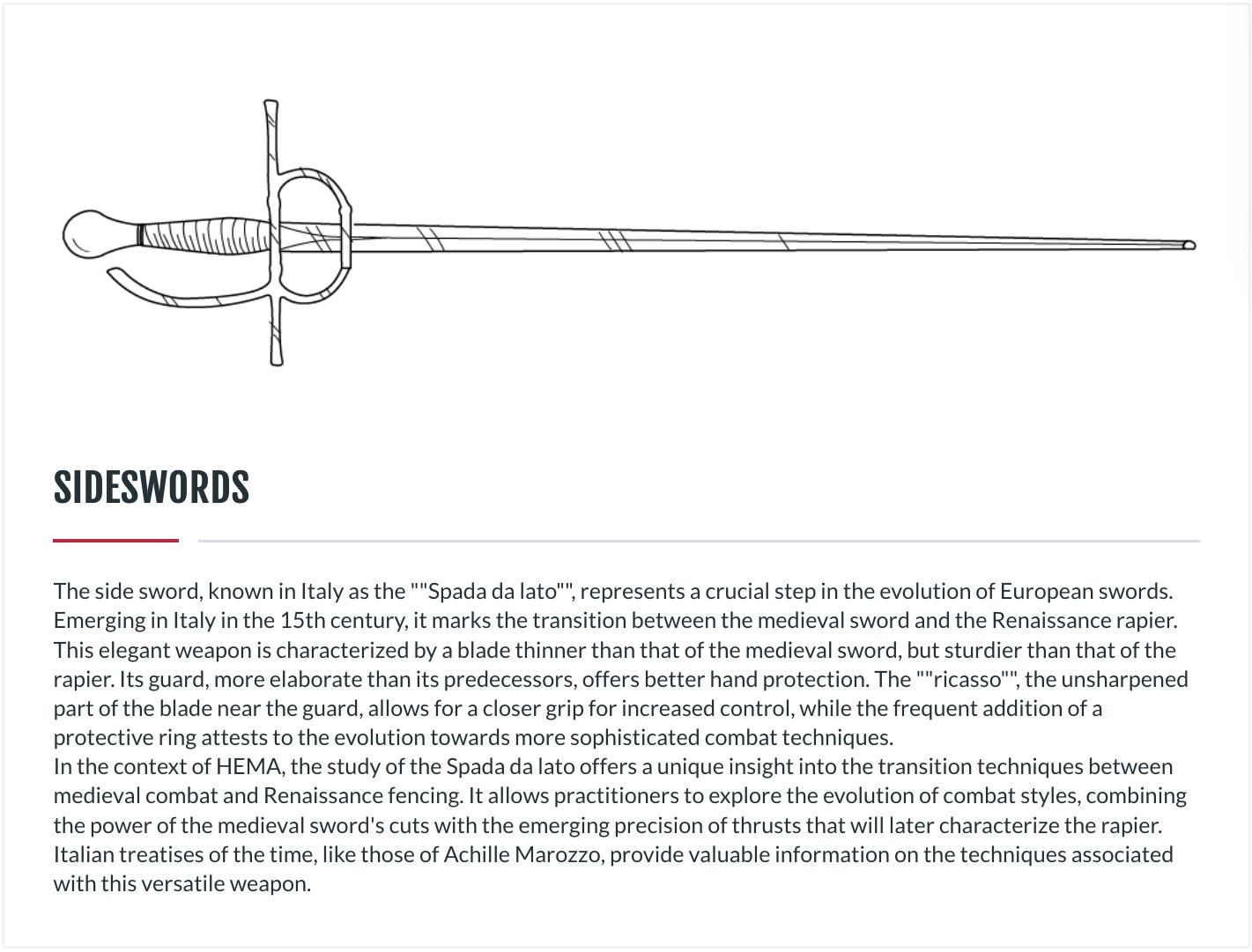

A good European store that sells HEMA gear, which I have used personally in the recent past. Switching the language between Italian and English, we can read the translation of (plural form) spade da lato as rapiers.

But switching the language when looking at the products themselves under the spade da lato category, shows that while some cup-hilt rapiers are labelled in Italian as striscia, and some are labelled as rapiera, they are still just rapiers in English. And yes, I am ignoring the term rapisarda.

But if spade da lato translates as rapiers, what do we call sideswords? Well silly, that’s spade laterali (lateral swords), also known as spade da lato. That’s spada da lato sidesword and not spada da lato rapier. Don’t let the fact that they are spelled in the same way and are pronounced in the same way to confuse you. Or we just move on.

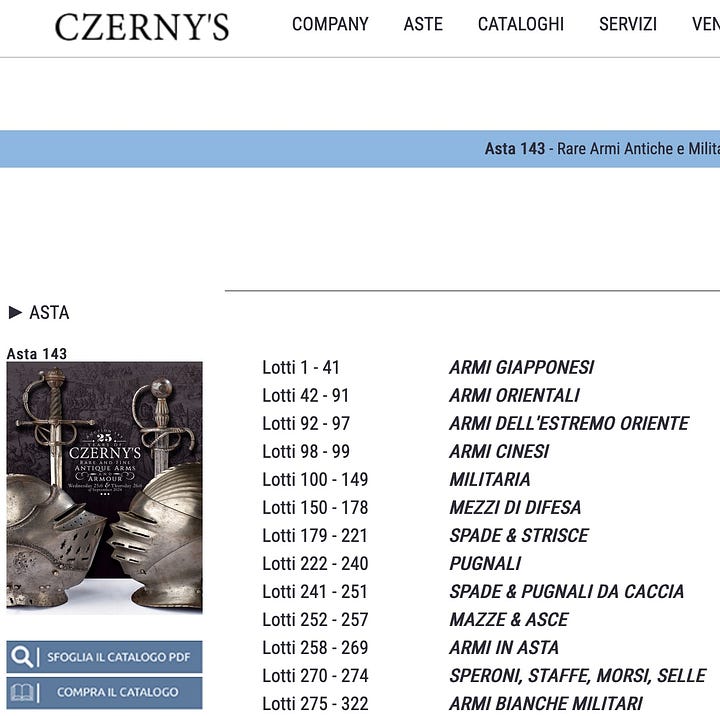

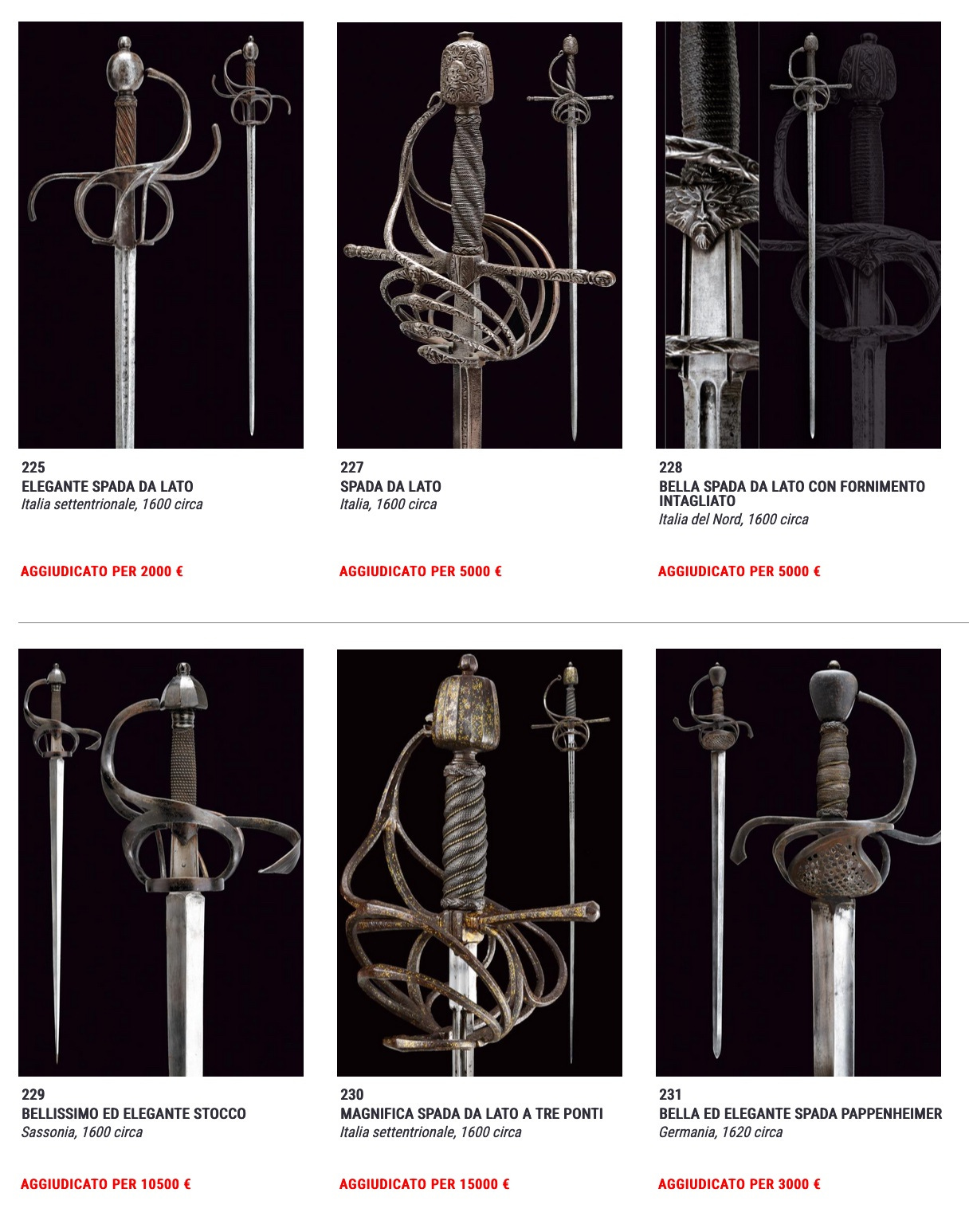

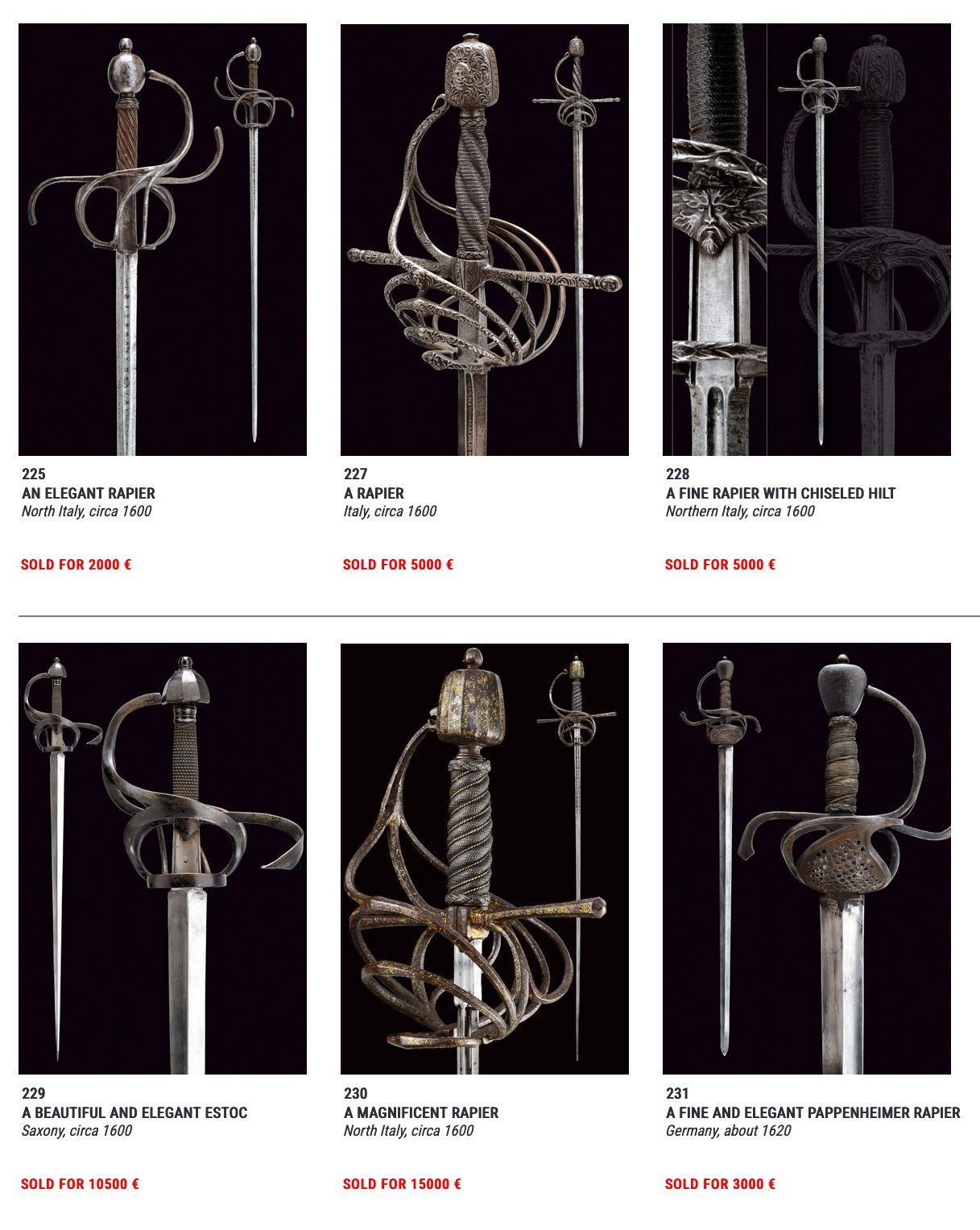

Czerny’s Auction House

An auction house should help us understand the use of these terms better. We see that Spade & Strisce (lot 179-221) translates as Swords & Rapiers. So strisce means rapiers. But except for stocco being translated as estoc, we see that all rapiers are mentioned in Italian as spada da lato.

Making Sense of Things

It is clear that in modern Italian, like in other languages, trying to classify swords into sideswords, rapiers and other neatly defined sword types results in confusion. Terms get used and reused for different swords in a very inconsistent way. This is due to the historical use of the terms, the use in the antique market context, and the more refined use in the new HEMA context. In the latter, we even see spade laterali (lateral swords) being adopted as a term, one obtained by translating from English the sidesword label in its sword by the side meaning, ignoring that itself was obtained from spada da lato. All this is done in an attempt to clarify the name of a particular type of HEMA weapon (i.e. the weapon used for Bolognese sidesword), which actually shows why a certain clarity is needed when naming swords. Moreover, some HEMA authors took the term spada da lato to mean wide-sword (from lato = wide), which clearly is not how Italians use this term in reference to swords, so in this case spada da striscia can be adapted simply as narrow-sword. We see that there is quite an arbitrary way to designate particular swords.

I believe that we need to dispense with the connection between sidesword and spada da lato in terms of a broad category, and only use sidesword in its Bolognese sense (and German and English sense when appropriate; seen as a regional variations of the same type). As a general category, spada da lato needs to be translated as sword by the side. And as a specific type, spada da lato just means sidesword. For example, if we use:

spada da lato = sidesword

striscia = streak-sword

rapiera = rapier

stocco = estoc

for their respective type of swords, then the estoc, rapier, streak-sword, sidesword are all swords by the side. Otherwise, if we keep sidesword as a broad category, we would need to include the rapier as a subcategory to sidesword. So we would have estoc-sidesword, rapier-sidesword, streak-sidesword, (Bolognese sidesword) sidesword. I lean towards the first approach, which narrows the span of the sidesword term, but clarifies its use in the process. For example, considering their archetypical tools, Marozzo uses the sidesword, Capoferro doesn’t as he uses the rapier, and Agrippa before him uses the streak-sword.

Some sources (not discussed here), would prefer to use spada as sword, spada da lato as sidesword (in its sword by the side category meaning that would span from 1450 to 1650; so from the tradition of Dardi to the one of Alfieri), stocco to refer to more triangular profiled blades with an acute tip mounted either on simple or complex swept hilts (so a blade designation rather than a sword type), and spada da lato a striscia (or simply striscia) to refer to late 17th century cup hilt rapiers with narrow blades that cannot realistically cut (so more Destreza traditions and later). However, as we see above, this is not how it is used in reality, and it just shows again the arbitrary nature of assigning names and classifications.

The lesson I extract from all this is that I shouldn’t feel too bad in adapting the names when I translate them from Italian, as they are not some well-established sacrosanct terms in their original language. Another lesson is that a weapon designation makes sense in the context of its use, as a way to anchor the need for that designation.

I will make a subsequent post describing why I consider we need the introduction of the streak-sword as a designation separate from sidesword and rapier, and why I think it will help clarify the HEMA weapon scene and anchor the labels into respective fencing traditions. But I wanted here to showcase why it is OK to adapt and implement names beyond simple translations found in Italian sources, be they new or old, and use those only as the starting point in naming swords and sword types.

"Striscia" is usually used in hilt typologies to describe bars, especially wider ones. The equivalent term in English is "ribbon". So Spado a Lato a Striscia denotes a sword with a swept, usually.

"Le spade da lato al museo Stibbert" is a good book which uses this convention.