Sword typologies are not new. We have the Oakeshott typology for medieval swords, the Elmslie typology for the description of single-edged blades, the Petersen typology for the hilts of Viking age swords, A.V.B. Norman typology for rapier hilts, and even a proposed classification of tessaks (dussack). But all these typologies are based on morphological aspects, on the shape of the blade, or the shape of the crossguard and the shape of the pommel. These typologies don’t take function into account that much, if at all. From my perspective, this latter aspect is the most interesting one to consider, but also the most difficult one to account for.

In general, if you have a population (of swords, animals, rocks, etc.), the idea of classification is to split this population into a series of disjoint divisions that groups individual elements by some common characteristics. The disjoint aspect ensures that one element is assigned only in one division, which helps keep track of individual elements even if the classification itself may be imperfect.

I think that using this classical approach for swords is bad, and leads to endless discussions about the actual type for a given sword. Is a rapier (which is defined on the hilt) with a broad blade actually a broadsword (since this is defined on the blade), or a sidesword (because it’s a cut-and-thrust sword with a relatively broad blade and complex hilt)? Which of the sword’s elements take precedence in a classification, the hilt or the blade? Worse still, most people forget that they are proverbially comparing apples and oranges when they engage in these discussions that mix different typologies. And yes, while ordered nested divisions may help with this (e.g. first division on the edge, second on curvature, third on the hilt, fourth on the culture, and so on), it would lead to a very cumbersome typology for practical use.

I prefer an alternative approach, which I will describe next, that results in the identification of sword types that can be then assigned to swords in a non-unique way.

My Approach for Defining Sword Types

Imagine we have a population of swords, which as we will find out later, contains at least three types, type A, type B, and type C (like in the drawing below). Each type may be defined in the same way (e.g. on the length of the blade), or defined on different attributes (e.g. some on the hilt’s complexity, others on the blade’s curvature). It makes little difference, and we’ll just say that this population of swords exists naturally, regardless of our subsequent definitions. Our task now is to identify these types.

Conceptually, we start by choosing the defining characteristics we have in mind for a sword. Then, we find or postulate a representative archetypical example, and we make a distribution around this archetype by ordering the entire population by how well it matches it. By definition, the archetypical example will be at the peak of the distribution, and we will find worse and worse swords of the type in question as we move away from the ideal. For example, if we say that type A represents swords with blades that are 90cm in length, give swords a score of 1 if they do match this ideal, and score them sub-unitary if the blades are less or are more in length depending on the deviation from our 90cm ideal, by plotting this score as a function of the difference in length, we will get something like the distribution I drew above.

Now, let’s say that we found the three distributions, denoted by the blue, red and green solid lines. Please note that each distribution obtained covers the entire population of swords, ordering it with respect to their distance to their prescribed archetypical example. Each distribution has a maximum of 1 and decreases in value, and is shifted as above (e.g. we looked in our previous example at deviations from 90cm in the length of the blade for type A, but we plot the distribution by shifting it with this value so that the peak rests at the value of reference and the figure’s boundaries cover the entire population). In an attempt to have three disjoint types and call it a day, we could then split the entire population by the intersection points between distributions (denoted by the dotted black line in my drawing), but this would be wrong. At best, for example, these intersection points just represent swords that are equally type A and type B, or equally type B and type C. But since the choice of archetypes (i.e. defining characteristics) for each type is arbitrary, we are back at the problem of comparing apples and oranges. In fact, if the individual types are defined on separate aspects, we can imagine that the archetypical sword for type A (one with a 90cm blade) is also the archetypical sword for type B (let’s say, a grip of 8cm). The discussion if the mentioned sword is type A or type B is not just flawed, it’s wrong! Swords can match multiple types at the same time, and they can do that quite well.

What we actually need to do next is to take a given distribution, and cut away the score values that are too small to matter compared to the desired archetype (the cut-off boundaries being denoted by dash lines of respective colours). We call a type whatever falls inside this resulting interval. We see that in this approach, types can overlap, and this is OK. This classification just helps us identify a particular sword type and does not serve to split the entire population into neat sections. Since the cut-off thresholds are arbitrary and discussion dependent, if an individual sword falls outside a threshold, it can still be included as an atypical example if so desired.

Considerations for Assigning a Sword Type

In practice, it’s better to assign upper and lower thresholds for desired characteristics than to provide the ideal archetype. This is particularly useful for physical measurements since we are not actually going to compute distributions. In the end, we just want to know if measurements fall inside an interval we have in mind or not.

A sword type should include a fencing tradition, or specify the lack of one. In a broader sense, I believe that the philosophy behind the design and the use of a sword type should be stated. With the intent behind a type being stated, we can clearly see if a particular sword fits that type or not, and to which degree if yes. For example, the same hilt decorations can be used for different sword types, but having even a bit of knowledge of different fencing styles is enough to inform us if a sword makes sense for a particular fencing tradition. And even if it does, does it fit that tradition as well as other swords, or only tangentially? This is the part that cannot be defined from measurements on the sword, and where assigning a conceptual score compared to an ideal becomes more important.

Assigning a score is quite relative, as different people can have a different ideal in their minds. However, this serves to be honest with the arbitrary nature of assigning types (i.e. we effectively score something even without thinking) and puts the process into the forefront. People debating why a particular sword fits better in this tradition or in another can help elevate the discussion from simple blade measurements.

There is another benefit to my approach. You can define a type (e.g. sidesword )and the desired thresholds and extract all the swords that match the criteria, then compare what you have in mind with the rest of the sword population (e.g. the population of Italian swords from 1500-1530). For example, identifying a lot of swords that make sense in the context of a particular fencing tradition would show that the mentioned tradition was something widespread and not just a niche one.

Last on this, I like to call types that match well historical developments in swords as natural types, and types that are too broad to be useful on their own as category types (droping type when unnecesary). For example, I will call the four swords displayed below as being part of the swords by the side category, but each one represents a distinct natural type that made use of the fencing tradition developments of their time.

Considerations on Naming Sword Types

It is quite common to label sword types via letters or a combination of letters and numbers, and indeed, any naming convention will suffice. Yet, I prefer to think of ways to devise representative names for natural sword types that match a historical period and a fencing tradition. However, the reality is that names that don’t make sense to people will not be used. Moreover, any naming convention that will try to repurpose names that go against their established popular use is doomed to fail.

For example, translating spade da lato as swords by the side to capture the generic category should work. Some people may think of it as a strange translation, but I believe that this strangeness will help to associate it more with the generic concept of a sidearm than the term sidesword, which can help alleviate the naming confusion.

However, using streak-sword to refer to the more thrust-oriented swords that succeeded the sidesword and preceded the rapier will not have success. Historical swords don’t follow a clear-cut pattern, nor do they disappear when new types emerge. Since by my approach, multiple types can be assigned to the same sword, people will just use one broader type and leave it at that. This is why I should translate spada da lato a stricea as streak-sidesword instead of streak-sword. Streak as a prefix can act now as a way to narrow down the type, and if people drop it in favour of a more generic interpretation of the term sidesword, we are just recovering the status quo (nothing is lost, yet nothing is gained either, which is what I am trying to do here).

In the same spirit, I will use the field designation that I used in the past for field-sword in the context of a field-sidesword. I want to use field-sidesword for sideswords that emerged from the field of battle and were used in or inspired the development of Bolognese fencing traditions. This contrasts the later developments that emerged with the knowledge of the traditions and may have been adapted to better suit them. Again, if people drop the prefix field, we are left with the sidesword term used today.

As a note, Chris Adams made a comment that stricea, which I chose to translate as streak rather than strip, can be used in its ribbon sense and be associated with a particular wider sidebar style for the hilts. I believe these would look like the ones just below. Not only do I agree that this is a strong contender for the emergence of the term in the Italian sword vocabulary, but it also makes sense to me for the term to have drifted to refer to narrower blades and rapiers, since these were the swords used when the thrust became dominant. Since these hilts emerged at the same time when blades became longer and narrower, it would be funny if I were to adopt the same name used in the period for the same type of swords but for a different reason.

Swords by the Side Types

People already separate between sideswords and rapiers as being different, so at this point, I see the following natural types:

Swords by the Side: the category type for one-handed swords carried as side-arms

Sideswords: the broad type for cut and thrust swords

Field-sidesword: the early type emerged from the use on the field of battle

Sidesword: the core type developed for cut-focused fencing traditions

Streak-sidesword: type developed for a more balanced cut and thrust use

Rapiers: the broad type for thrust focused swords

Line-rapier: long blades, focused on blade deflections and on-line thrusts

Circular-rapier: focused on blade disengagements and off-line attacks

Transitional-rapier: lighter rapiers used for fast disengagements and thrusts

I will look at sidesword and rapier types in the Italian space between the late medieval and early modern times. I won’t look here at hangers or other field-swords that fall under the swords by the side category. I will look for museum examples with pictures where I can see the entire sword. Since I want to look at swords by the side that best suit particular Italian fencing traditions, I’ll focus on swords made in Italy unless specified, and leave Spain and Germany aside for the most part. As a small note, while early Spanish sidesword traditions are quite well separated from the Italian ones, by the time of the rapier, due to the actors involved in the Italian wars, the mixing between Italian, Spanish and German traditions intertwined to a much larger degree.

Note:

If you consider a particular piece to belong to a different type, that’s fine, just remember that a sword can have multiple types. And remember that a sword can be an atypical member of a type if it falls outside the stated thresholds. Last, remember that I want to concentrate on the use and not just morphological characteristics.

Abbreviations:

TL: Total Length, BL: Blade Length, BW: Blade Width, GL: Grip Length, W: Weight

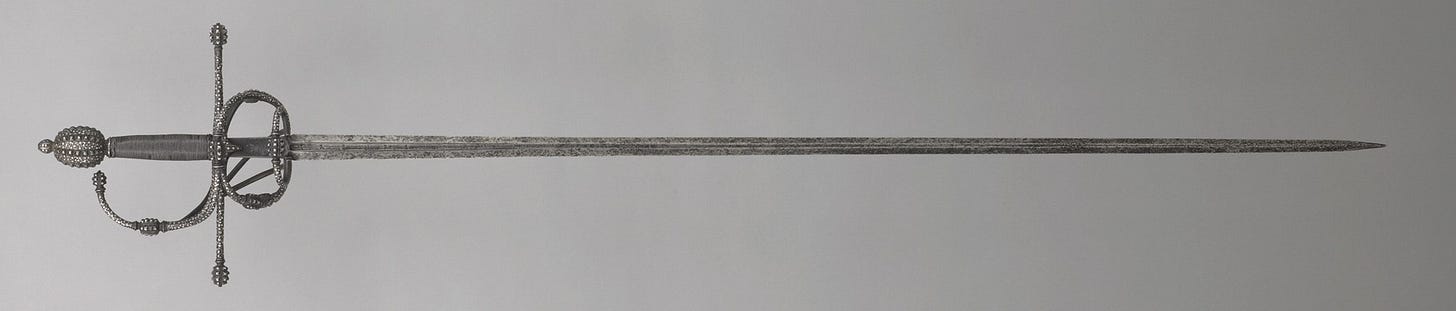

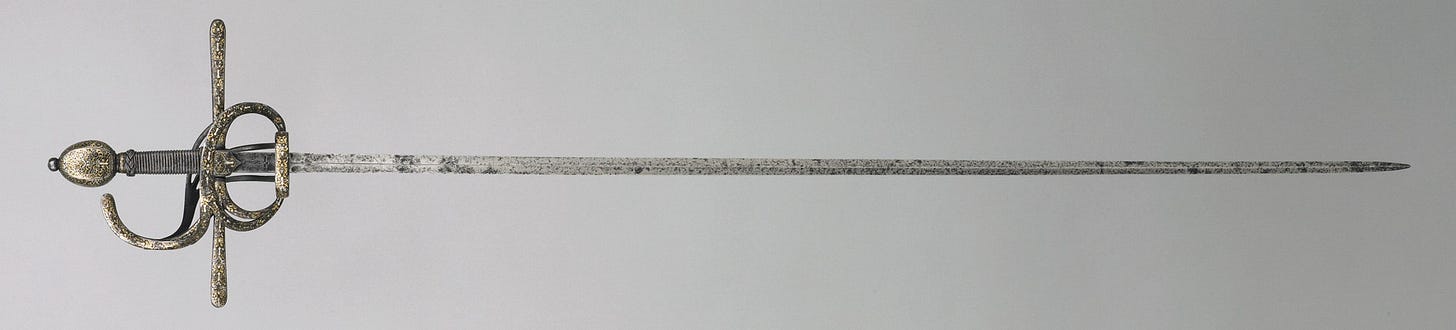

Field-sidesword

These are sideswords that developed naturally on the field of battle. We can consider them as swords that formed the basis for the sidesword fencing system. Unlike other infantry swords that tend to be shorter, and which were used by archers or other types of troops, these tend to have a longer blade. To reflect this aspect, I am using the name field-sidesword.

Characteristics

Blade Length: 85-95cm

Blade Width: 4-5cm

Weight: 1000-1200g

Starting Year: 1350

Fencing Traditions: the field of battle, start of Dardi’s Bolognese tradition

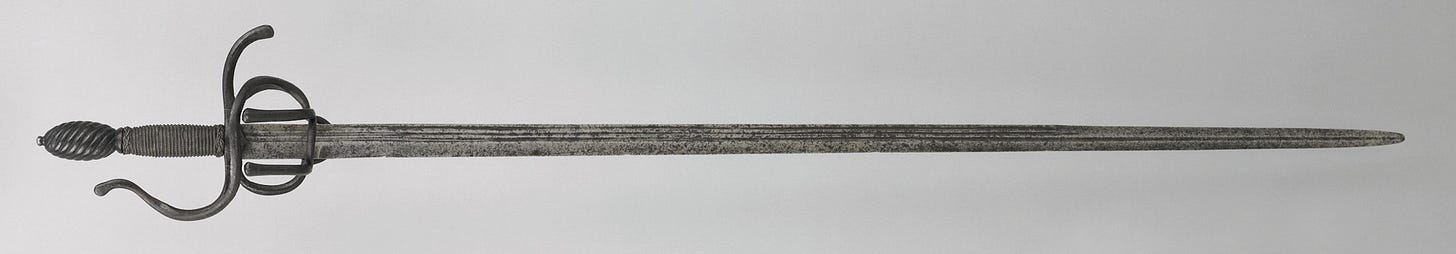

As general characteristics go, they tend to have wide blades of hexagonal cross-section, which makes them quite good for cutting. They have an abrupt point at the tip, so while one can thrust with them, this shows an optimisation for delivering cuts with a broad tip. Considering overall weights close to 1000g, the relatively long and wide blades indicate that they are quite thin, again conducive for the cut of soft unarmoured targets.

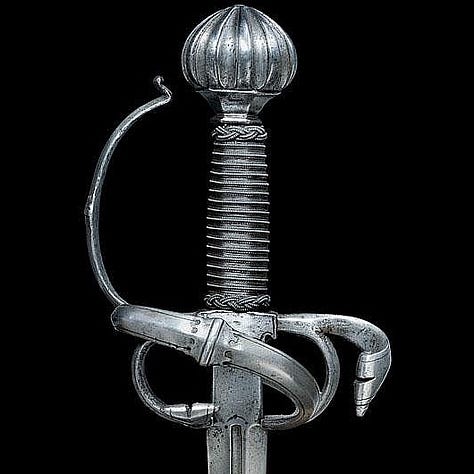

The hilt is simple, with a long grip, having at most a finger-ring on one side of the cross-guard. The blade has a ricasso, so it accommodates fingering the cross-guard. The long grips and single finger-ring can be an adaptation to allow the use of an armoured gauntlet, while also protecting the finger during unarmoured use. The longer grip can also allow one to balance a longer blade with a lighter pommel, keeping the sword’s overall weight in check. However, since the grip is quite long, one can hold the sword by resting the pommel at the base of the palm and extending the finger to barely cross the crossguard with only the fingertip. This would allow for finer control of the blade at the expense of power in the cut and can be seen as the start of experimenting with using the sword in unarmoured combat.

In later periods, we can still see a wide and long blade with an abrupt point at the tip for this type of sideswords that is employed in a militia context. While we can see a slightly more complex hilt, with a knuckle bow, the notable change is the shorter grip, in line with later sidesword developments. Beyond the cultural style aspects of the pommel and fittings, these remain simple swords that carry on their infantry origins.

* Numbers should be seen as an estimate, and are for LK Chen’s reproduction, which made use of the original sword’s measurements provided by Matt Easton.

** Tip may have been broken and rounded off.

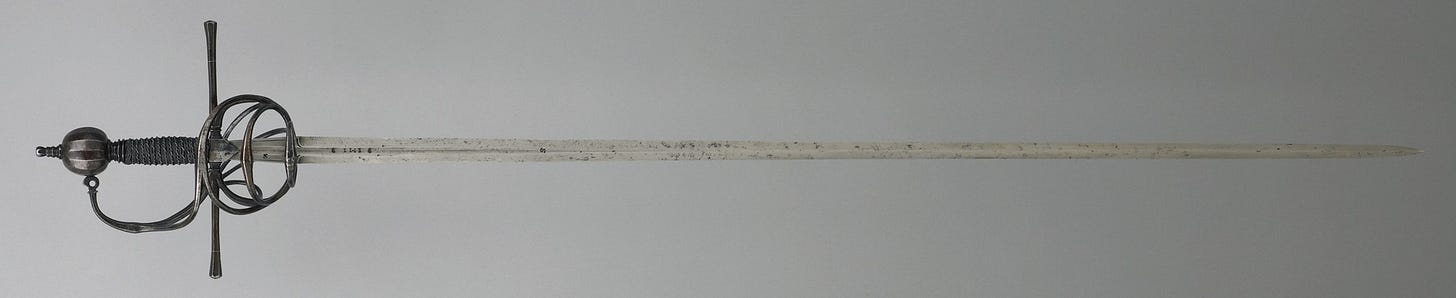

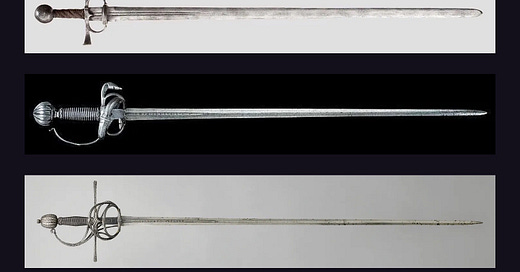

Sidesword

These are the sideswords used to form the core of the Bolognese fencing tradition. Since this is the default type, the core to what we compare all other developments with, to denote this fact we should simply call this type as sidesword.

Characteristics

Blade Length: 85-95cm

Blade Width: 3-4cm

Weight: 1000-1200g

Starting Year: 1490

Fencing Traditions: di Luca - Anonimo, Manciolino, Marozzo, Viggiani, dall'Agocchie

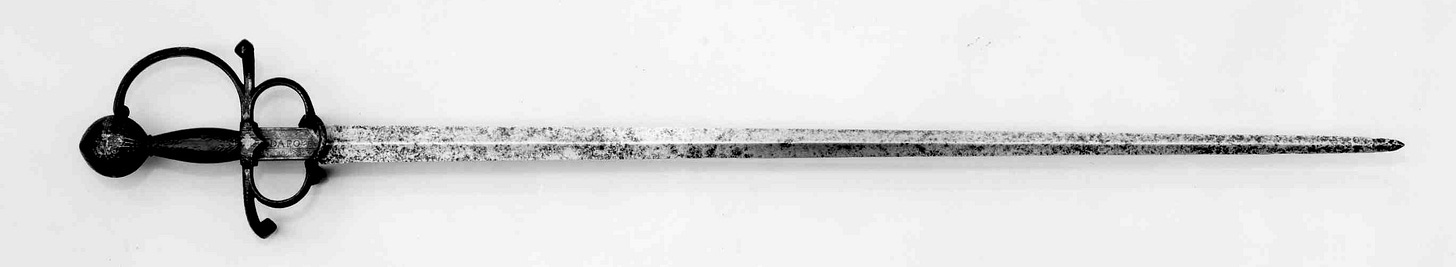

Compared to previous iterations, we see blades that become a bit narrower, but the emphasis is still in the cut, and we still see a preference for the spatulate tip that facilitates cutting with the tip of the blade. Naturally, thrusts are still possible for unarmoured targets. The grips become shorter, showing that there’s a need to prevent interference with wrist rotations. We also see side-port rings or langets to stop a sliding blade from reaching the hand, and we see the use of knuckle bows becoming more prevalent. There is also a larger variation in styles as they spread through Italy.

*Italian made, but influenced by the Spanish style, which explains the atipical blade.

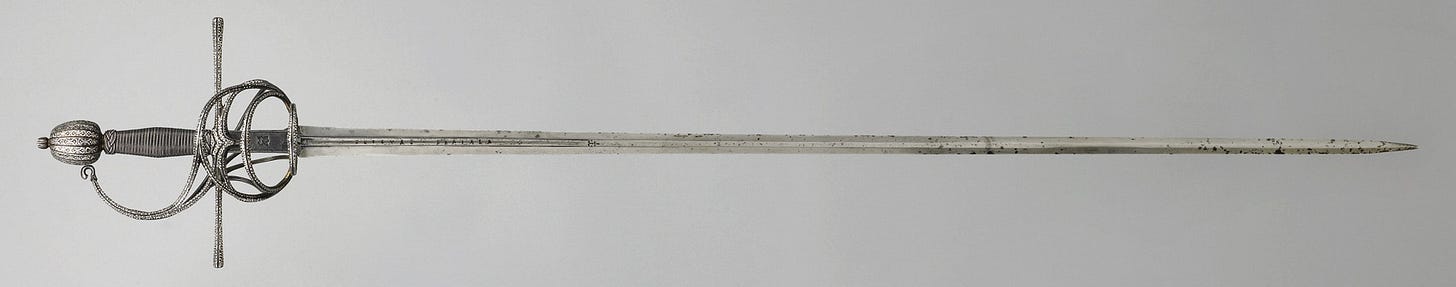

Streak-sidesword

As time moved on from the start of the 16th century, and fencing began to incorporate the thrust more and more, we see a sidesword that archives the balance between the cut and the thrust. The lunge becomes part of Scherma and guards change to a certain degree to promote keeping the point towards the opponent as much as possible. At the same time, we see more side-sweeps being added to prevent hand cuts, either during a bind or as part of hand-snipe attacks. Some of these sweeps are broad, ribbon-like in style. Either as a coincidence or by design, the term striscia is used as spada da lato a striscia. Striscia can be translated into English as strip, streak, or ribbon. Regardless of its past intent, since I want a term to capture the fast movement of a lunge, I chose to translate striscia as streak, which will capture the essence of metal sweeps, the longer and thinner blades, and also the sense of “to move very fast in a specified direction”. As such, I will label this type as streak-sidesword.

Characteristics

Blade Length: 95-105cm

Blade Width: 2.5-3.5cm

Weight: 1000-1200g

Starting Year: 1530

Fencing Traditions: Aggripa, di Grassi, Palladini

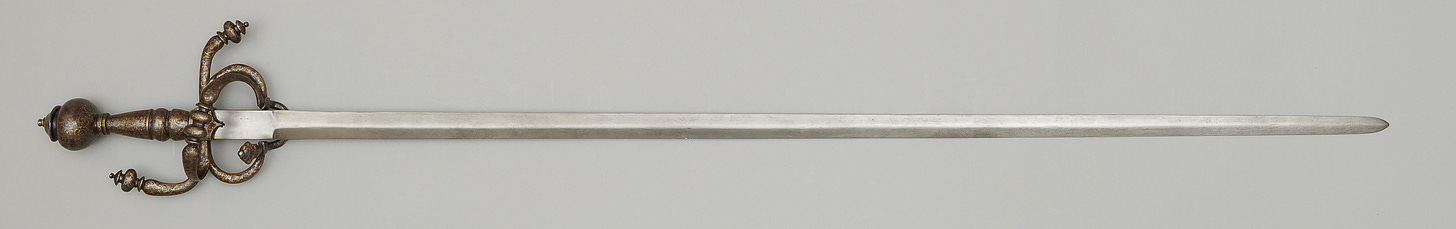

For the streak-sidesword, we see longer blades on average, and we see even narrower blades with acute tips. In fact, the thrust becomes so important that we see the incorporation of diamond cross-sectional profiles towards the tip of the blade. However, these blades are still capable of cutting much better than later blades we see mounted on rapiers. A characteristic blade has a square ricasso that leads into a hexagonal cross-section for the strong part of the blade and transitions towards a diamond cross-section for the weak part of the blade.

The hilt is also more complex, but with quillons that are quite small and twisted around the hilt. This can facilitatete wrist cuts, hinting that these are still in play. In fact, most streak-sideswords would qualify well as just sideswords. But the intent behind their design to facilitate the thrust is clear.

*The blade is from late 1500s.

**Measurments estimated by assuming a 8.5cm long grip.

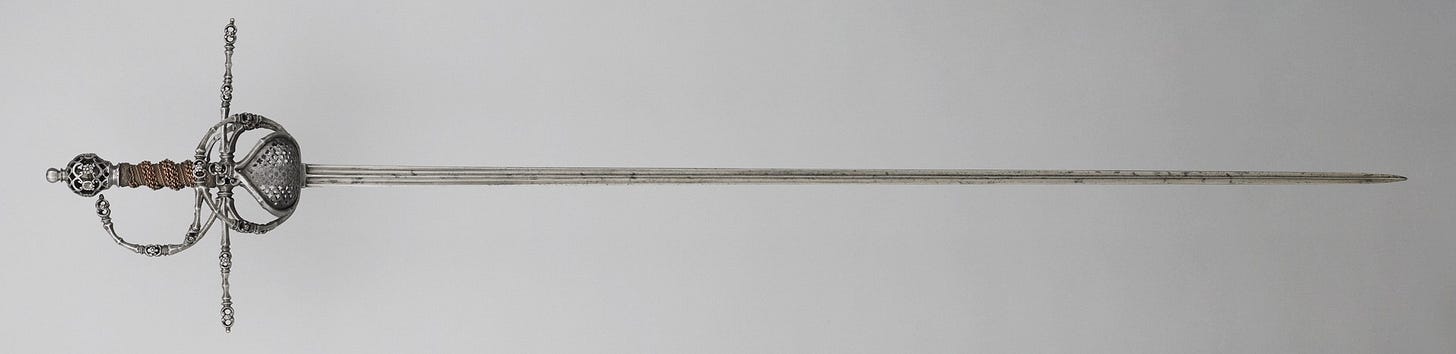

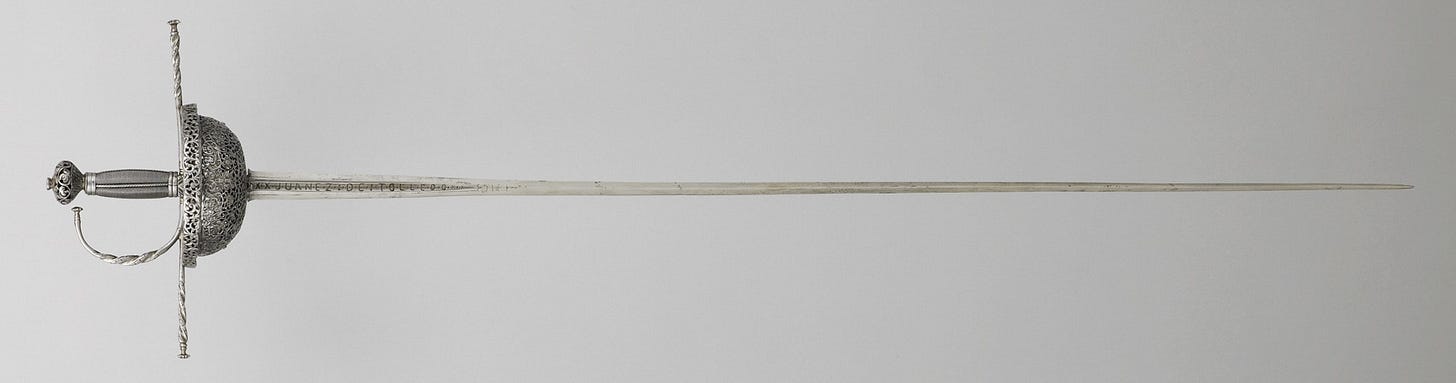

Line-rapier

By the turn of the 17th century, we see the thrust dominating the Italian Scherma. Blades become even narrower and even longer, and swept-hilts become even more complex. These are the rapiers as we see them today. However, two schools of thought also develop, the Italian Scherma that favours in-line footwork and thrusts after positioning the hand to deflect the opponent’s blade during the lunge, and Spanish Destreza that developed circular footwork and off-line thrusts after disengaging the opponent’s blade to gain control. The rapier that works better for Scherma, which favours in-line attacks, can be called a line-rapier.

Characteristics

Blade Length: 105-125cm

Blade Width: 2.2-2.8cm

Weight: 1200-1400g

Starting Year: 1580

Fencing Traditions: Fabris, Giganti, Capoferro, Alfieri

The characteristic feature of a line-rapier consists of a really long blade. We also see a narrow cross-section for the blade, and the cutting power of the rapiers is given by the speed of its tip than anything else. To balance such a sword, heavier pommels are needed, and grips sometimes become longer to help in this aspect. However, the point of balance is further towards the tip of the blade, which extends the strong part of the blade and gives the rapier more control in the bind. Regarding the hilt, we also see an explosion of styles, culminating with cup-hilts, however, married to the same long and heavy blades.

Circular-rapier

La Verdadera Destreza and the use of circular footwork is seen as a Spanish development. However, Spain was much larger in those times, occupying the Netherlands and a good part of Italy (n.b. oversimplification of facts for effect). This allows us to incorporate this tradition into Italy and look at rapiers that were optimised for this approach, referring to them as a circular-rapier.

Characteristics

Blade Length: 105-115cm

Blade Width: 1.5-2.4cm

Weight: 1000-1200g

Starting Year: 1590-1640

Fencing Traditions: Thibault, Masters in Destreza

Circular-rapiers seek to have a better tip control, and as such, prefer a lighter blade. They are of a lower overall weight, have even narrower blades than line-rapiers, and have slightly shorter blades to facilitate a nimbler movement. When circular-rapiers emerged, they had sweep-hilts, and only later ones incorporated shell or cup-hilts. The development of cup-hilts can be seen as a necessity for the circular-rapiers, which are held much more in front of the body rather than on its side. Last, just like the Spanish used line-rapiers, so did the Italians used circular-rapiers.

*Hilt, possibly Italy and decorated in Milan, blade made in Toledo, Spain

**Seen as being made in Spain or Italy, showing the mix of styles.

***Spanish, provided as reference and comparison with the Italian cup-hilt rapiers that were assimilated in the Italian peninsula at that time.

Transitional Rapier

This is seen as the evolution of the rapier into the early modern era, as the rapier morphs into the smallsword. This is why this is simply called a transitional rapier.

Characteristics

Blade Length: 100-115cm

Blade Width: 1.5-2cm

Weight: 700-900g

Starting Year: 1620

Fencing Traditions: Charles Besnard, Johannes Georgius Bruchius

Light weight to facilitate quick movements and improve the ease of carry. We see low weight thin blades optimised for the thrust with almost no cut capacity. The fencing style can be seen as a mix of Destreza and Scherma, with more in-line work, but with disengagements and quick thrusts. These are not Italian traditions per se, but at the time of their emergence, we see a large blend of styles due to the rule of large empires.

*Hilt, probably North Europe, and blade, probably Germany.

**Hilt, probably North Europe, and blade, probably Germany.

***Probably made in France.

Final Thoughts

In the end, why is this useful? Well, why don’t we call everything just swords? We don’t because we want clarity. And there is the clarity in the commercial sense, of buying and selling swords with the correct expectations. And there is clarity in the practitioner's sense, of using period-appropriate swords for a particular tradition. I want to train in the Bolognese tradition, to absorb elements of Agrippa, and study Capoferro, only to explore a little Destreza to know how to fence against it if nothing else. Besides, swords are expensive. If I want to have an antique, a good sharp and a good trainer for each type I want, I better first understand what I mean by type. ;)

My approach as stated here was the result of a few months of thinking and a few weeks of preparation. It is not perfect and can be improved in the future. Don’t hesitate to comment, to state your opinions and disagreements. Overall, I see it as a starting point and I hope I will have the chance to improve on it. Notably, I want a typology that accounts for the use of swords, and learning to use a sword and thus extract a better context for the use of a sword is not a quick process.

Incredible work, I've only had time to really digest some of this, and I have to say this is a masterpiece, well done!